News

Historians Teach More and Larger Classes, but Make Less Use of Technology

Historians teach more and slightly larger classes than faculty in most other disciplines, but make less use of technology, according to the 2004 National Study of Postsecondary Faculty.

Alongside the valuable data on who teaches history in two- and four-year colleges and universities and what they earn that we reported in the March 2006 Perspectives, the new study also provides important insights into some work practices of historians, and allows us to see them in the larger context of academia.

Some of the findings merely reinforce common perceptions—that undergraduate classes at liberal arts colleges are much smaller than in other institutions, that senior faculty spend significantly less time teaching undergraduate students, and that historians make less use of technology in their teaching than other disciplines. But the report also offers evidence that may seem slightly less obvious—that an unusually high proportion of historians identify teaching as their primary activity, that graduate courses in the history are among the smallest in academia, and that there are only modest generational differences in the use of technology in the classroom.

Teaching: The Course Load

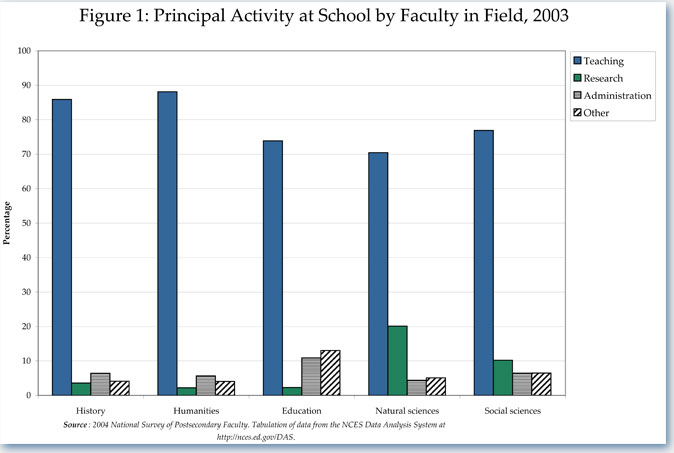

Despite the common perception that the history discipline is unusually wedded to research and monographic scholarship, most history faculty identified their principal employment as teaching. Almost 86 percent of history faculty reported that teaching was their main activity at the school. Just 3.6 percent reported their principal activity was research, while 6.4 percent indicated it was administrative work, and 4.1 percent reported it was some "other" activity (Figure 1).

This was significantly higher than the average for all fields, where just 73.8 percent of the faculty indicated teaching was their primary activity. History finds itself among the humanities on this point, as 88.1 percent of the faculty in the humanities reported they were principally doing teaching.

The smallest proportion of history faculty reporting teaching as their principal activity were at universities with doctoral programs. At private universities with doctoral programs, 77.7 percent of the history faculty reported teaching as their primary activity, while 79.6 percent of the faculty as public doctoral institutions so reported. This was modestly lower than the proportion of faculty at four-year institutions that do not confer doctoral degrees, as nearly 85 percent of the faculty at both private and public institutions reported teaching as their primary activity. Among history faculty at two-year institutions, 97 percent indicated teaching was their primary activity.

While we cannot say whether these perceptions lead to or follow from actual work patterns, the study does clearly show that history faculty teach more and larger classes than faculty in most other disciplines.

On average, historians in academia taught 2.4 courses in the fall 2003 term. This compares to an average of less than 2.1 classes among faculty in all fields. Among faculty employed full-time, historians have the 11th highest teaching load (among 26 disciplines in the survey), with an average of 2.8 classes in the term, as compared to 2.5 classes for faculty in all fields. This lags behind vocational fields such as computer science and business, and a few of the other humanities fields, such as fine arts, philosophy, and English.

Historians employed part time also taught a slightly larger course load than faculty in other fields, averaging 1.7 classes in the term as compared to 1.5 among all fields. As a result, history faculty employed part time had the sixth largest average course load among the disciplines.

As one might expect, there are large differences in the teaching loads for historians depending on the type of college or university that employs them. History faculty employed full time at two-year colleges taught an average of 4.2 courses and faculty at four-year nondoctoral institutions taught 3.2, while their counterparts at four-year doctoral programs taught an average of just 2.2 classes in the fall 2003 term. Faculty employed part-time at 2-year institutions taught an average of 1.8 courses in the fall term, while historians employed part time at doctoral institutions taught an average of 1.4 courses.

Teaching: The Class Size

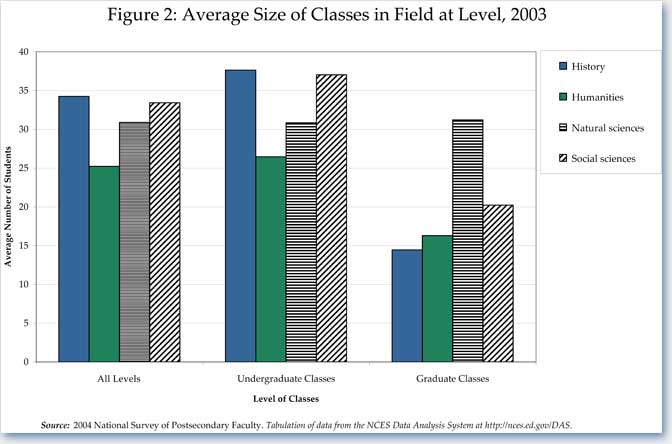

The difference between history and other disciplines does not end with the number of courses they teach, as they generally teach larger classes than faculty in the other disciplines as well—at least at the undergraduate level (Figure 2). Historians reported teaching an average of 37.6 undergraduate students per class, which compares to an average of 27.7 students in all undergraduate classes. This places undergraduate history classes as the fifth largest among the disciplines, as the field lagged behind just a few other science and social science fields—the health sciences, biology, psychology, and economics.

Like the differences in the number of classes taught, the number of students in those classes varied significantly depending on the type of institution. Of course, there are still very profound differences between the history class sizes at different types of institutions. At four-year colleges with doctoral programs, undergraduate history classes had an average of 53.8 students. In contrast, undergraduate classes at four-year programs at institutions without doctoral programs averaged 26.9 students per class, while classes at two-year programs averaged 27.5 students. Not surprisingly, the smallest average undergraduate history classes were at liberal arts colleges, with 21.4 students.

In contrast to the class sizes at the undergraduate level, historians reported the second lowest average class size for graduate-level courses, with just 14.5 students per class. At the graduate level, the average class size in all fields was 25.6 students per class. In institutions with doctoral programs, the average graduate history class size was the smallest in any discipline, with just 13.3 students.

Obviously not all instruction takes place in a formal classroom setting. The data indicate that history faculty provide slightly more individual instruction (supervising students and independent study) than faculty in other fields. Among faculty employed full time, more than 40.5 percent of historians reported that they provided some individualized instruction. More than half of historians at the full professor level provided this kind of instruction. This is a slightly larger proportion than in other fields, where 38.6 percent of full-time faculty reported some individual instruction.

Not surprisingly, there are marked differences based on faculty members' rank. Assistant professors in history provided individual instruction to an average of 8.8 undergraduate students in the fall 2003 term, while full professors worked with an average of 3.5 undergraduate students. Full professors also provided individual instruction to an average of 3.1 graduate students.

Despite the smaller graduate class sizes and added individual instruction, historians reported a slightly larger average number of student contact hours than faculty in other fields. History faculty reported an average of 270 student contact hours per week (these and other figures in this section have been rounded off). Although this was slightly more than 16 hours above the average for all fields (253 hours), history lags well behind the health sciences—which average over 380 hours—and the social sciences, which average between 276 (in economics) and 311 (in sociology).

Teaching: The Methods

Beyond the questions of who (and how many) are being taught in history classes, the survey also provides some useful evidence on pedagogical practices.

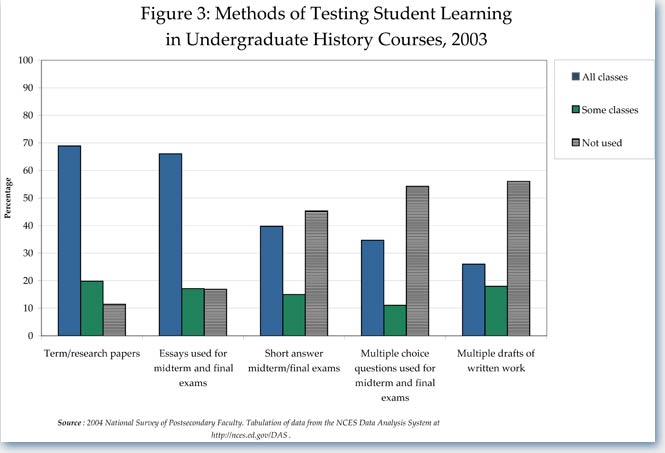

The most common methods for assessing student learning in undergraduate classes were research papers and essay questions on exams (Figure 3). Fully 68.9 percent of faculty said they used term and research papers in all of their classes, and 19.8 percent said they used them in some classes. An almost equal number, 66.0 percent said they used essay questions in all courses, while another 17.1 percent said they used them in some courses.

Part-time faculty and faculty at two-year institutions appear to be slightly more likely to use a range of assessment methods in their classes than full-time faculty or faculty at four-year institutions. For instance, while 74.7 percent of the history faculty at two year institutions use term papers in all of their undergraduate classes, less than 67 percent of the faculty at four-year institutions used them in all classes. And while 72.1 percent of faculty employed part time used term papers in all classes, just 66.9 percent of the full-time faculty did so. Similarly, 73.9 percent of the history faculty at two-year institutions used essay questions in all of their undergraduate classes, while 65.4 percent of the faculty at four-year institutions used them in all classes.

The survey indicates that on multiple choice tests there was much wider divergence. Just 34.6 percent of undergraduate history faculty said they use multiple choice tests in all classes, while nearly 60 percent of the faculty at two-year programs, and 52.6 percent of part-time faculty use multiple choice tests in all classes. In contrast, 61.4 percent of full-time faculty, and 70.3 percent of faculty at four-year programs conferring doctoral degrees, do not use these tests in any of their classes.

The survey thus offers evidence about a range of different types of assessment and a diverse set of practices. It does not, however, allow us to peer more closely at how these are implemented—the mix of these methods of assessment in particular classes, and whether different types of assessment are used more at the introductory and intermediate level.

Use of Technology

The survey also provides useful information on the different ways faculty use technology in their teaching. Contrary to what one might expect, historians are quite similar to faculty in other disciplines in their use of the World Wide Web for teaching, and in their use of e-mail to remain in contact with their students.

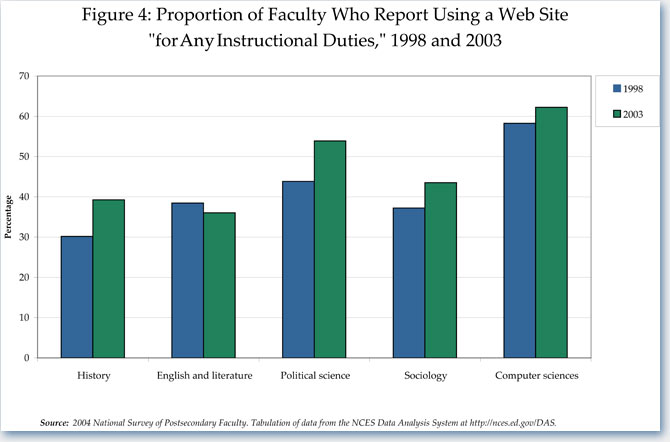

While 39.2 percent of the history faculty indicated that they use web sites "for any instructional duties" (Figure 4), this was just a tiny bit below the average among faculty in all fields, where 39.7 percent reportedly use web sites for their teaching. As one might expect, faculty in fields that tend to make more substantive use of computers as part of their regular work were more likely to make use of a web site for their teaching.

This use of web sites seems to be a modest improvement since 199,8 when just 30.2 percent of the faculty said they used the Web for any of the classes they taught. There was a slight change in the wording of the question that makes direct comparison a bit risky, but this does indicate some improvement. Needless to say, the question was not even considered for the survey conducted in 1993.

While many faculty in the field report that e-mail is a mixed blessing as a means of staying in contact with students, the vast majority in the discipline now do so, as 82.4 percent said they use e-mail to stay in touch with their students. This is actually a bit higher than among faculty in other fields, where 72.4 percent said they allocated some screen time to their students.

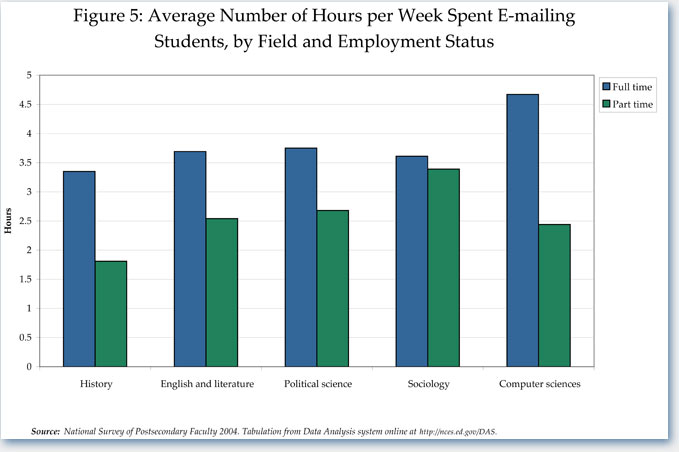

What is perhaps more surprising is the large amount of time spent e-mailing students—just a bit over three hours per week for full-time history faculty. Notably, however, since history class sizes are a bit larger than average, historians seem to spend slightly less time on e-mail on a per-student basis than faculty in other fields (Figure 5).

As one might expect, there seems to be a modest generational difference in who is e-mailing students. Among faculty under the age of 45, 94.6 percent spent some time in e-mail contact with the students, as compared to 85.3 percent of faculty aged 45 to 64 and 75.3 percent of faculty 65 and older. Similarly, faculty under the age of 45 were slightly more likely to have a web site for their classes—as exactly half of the full-time history faculty under 45 said they had such a web site. Curiously though, faculty over the age of 65 were slightly more likely to have a web site than faculty in the middle cohort, as 45.8 percent of the faculty over 65 had a web site, while among faculty between 45 and 64, only 42.7 percent had such a site.

Although more of them use the technology, younger faculty actually spent slightly less time in e-mail contact with students. When we limit our analysis just to full-time faculty, we find that faculty under the age of 45 spend an average of 3.1 hours per week in e-mail contact with their students, while faculty between the age of 45 and 65 spent 3.6 hours in e-mail contact with students.

These figures do not factor in the amount of time junior faculty have to spend just getting on top of their first syllabi and lectures, in addition to the work of getting the publications needed for tenure. Nevertheless, this does suggest less of a generational difference than one might expect.

Other Activities

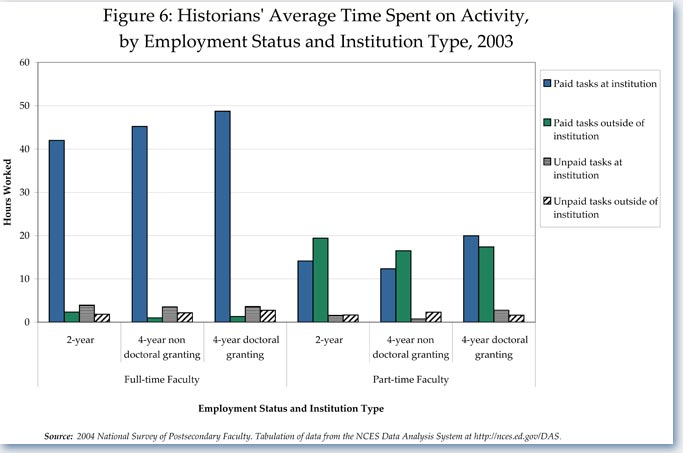

Even though most faculty consider teaching to be their principal work activity at their institutions, this can hardly belie the fact that schools often make other demands on their faculty's time. Once again, historians seem to be a bit more engaged than faculty in other disciplines. There is a marked difference between history faculty employed full and part time (Figure 6). Full-time history faculty estimated that they spent an average of 46.6 hours per week in paid tasks (teaching, class preparation, research, and administration) at the institution and an average of 1.4 hours per week in paid tasks outside the institution (including consulting, working at other jobs, and teaching at other schools). These faculty estimated that they spent an additional 3.6 hours per week in unpaid tasks at the school (such as "club assistance, recruiting, or attending institution events") and another 2.4 hours in unpaid professional service activities outside the institution.

In contrast, history faculty employed part time indicated that they spent an average of 14.9 hours per week in paid tasks at the institution and an average of 18.2 hours per week in paid tasks outside the institution. These faculty estimated that they spent an additional 1.6 hours per week in unpaid tasks at the school, and another 1.4 hours in unpaid tasks outside the institution.

In terms of paid and unpaid work at the institution, historians work an hour per week more than the average among all fields, and lag just behind the hard sciences, professional disciplines, and political science. The gap is actually wider in comparison to the other humanities and social science fields, as historians employed full time worked an average of nearly two hours per week more.

Given that extra work burden, it is worth reiterating the finding in last month's article that historians' earnings are significantly below the average for all fields. Clearly, compensation does not correlate to the time spent working for the institution.

Alongside the undercompensated employment at the institution, historians employed full time seem to provide an unusually large amount of unpaid service outside the institution. The 2.4 hours spent in service activities outside the school is the third largest of any discipline in the survey and more than a half hour in that activity. In this historians only lag behind the fine arts and are actually ahead of fields like law and education that notionally place a greater premium on service.

Aside from the differences in employment status, the only other marked differences seemed to depend on where they were employed. Full-time faculty employed at four-year universities with doctoral programs reported working an average of 56.3 hours per week. This was over four hours per week more than faculty at four-year programs without doctoral programs (who estimated they worked 51.9 hours per week), and more than six hours per week more than full-time faculty at two-year programs (who estimate 50.1 hours per week). Along most other measures—whether examined by rank, age, or gender—there were very few differences.

Publications

Finally, even though the numerical data suggest that teaching constitutes the bulk of the historian's job on campus, it would be foolish to deny that publications are still highly prized in the profession. The study does offer some information about the number and range of publications by historians, but unfortunately the way the questions were posed makes the results of limited utility for our field.

For instance, in asking how many books a particular historian has published, the survey questionnaire lumps together all types of books—monographs, textbooks, and trade books. So we can report clear differences between historians at different ranks—full professors had published an average of 3.2 books, associate professors 1.6, and assistant professors 0.7 in their careers, for instance—but we cannot measure some of the important differences in the types of books published.

We can also report that faculty at doctoral institutions report that they have published more of these books than their counterparts at other four-year institutions—at least at the associate and full professor level. Curiously, though, assistant professors in history at nondoctoral institutions reported that they had published 1.0 book to date, while assistant professors in doctoral institutions had published an average of 0.4 books. But since we cannot distinguish what type of books these might be, it is hard to assess whether this is a substantive difference in the march toward tenure.

The study offers a remarkably similar set of findings on the subject of articles published in refereed journals. Full professors at doctoral institutions reported that they had published an average of 17.6 articles in their careers, as compared to 11.1 published by their counterparts at institutions without doctoral programs. This was more than twice the numbers published by associate professors at the same institutions—8.6 and 4.4 articles respectively. Once again, assistant professors at doctoral programs had slightly fewer publications to their credit—2.6 articles, as compared to 4.0 by their counterparts in institutions without doctoral programs.

The difference in publication rates can be attributed at least partially to differences in age. The average age of full professors at doctoral institutions was almost three-and-a-half years more than their counterparts at nondoctoral institutions—allowing more time to publish articles and books—while assistant professors at doctoral institutions were a year-and-a-half younger than their counterparts—presumably allowing less time for publication. That does not, however, explain the difference at the associate professor level. Even though they have published fewer books and articles than historians at the same level in doctoral institutions, the average age of associate professors in four-year institutions without a doctoral program was more than four years older.

When asked how many of each type of publication they might have published within the past two years, the findings are much more similar, as full professors and assistant professors at the two types of four-year institutions had published nearly the same number of books and articles. The only notable difference was that associate professors at doctoral programs had published almost twice the number of articles in refereed journals as their counterparts in institutions without doctoral programs (an average of 1.3 articles as opposed to 0.8).

—Robert Townsend is AHA's assistant director for research and publications.

Tags: Teaching Resources and Strategies

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.