Archives

Digitizing the Fletcher Papers: A Unique Historical Experience

In July 2014, I traveled to Hollywood, Florida, to do research in a private, unprocessed collection of personal papers from the estate of Arthur Fletcher. Frankly, I did not know what to expect. Fletcher’s son, Paul, had moved the papers from a flooded basement in Washington, DC, after his father’s death. He told me they were safely located in a storage space that he visited every day. He was hoping to film a documentary about his dad with the assistance of faculty from one of the local colleges. With Paul’s permission to digitize the collection and a small grant from my university to cover travel and lodging, I hit the road for South Florida.

Arthur A. Fletcher (1924–2005), self-styled “father of affirmative action,” rose from poverty to advise four US presidents and, as head of the United Negro College Fund, help develop the slogan “A mind is a terrible thing to waste.” Along the way, he was wounded in Europe while serving under General George Patton, broke the color barrier as the first black player for the Baltimore Colts football team, and developed a comprehensive self-help program for the African American underclass. But what makes Fletcher’s story even more compelling is his remarkable return from a midcareer crash. After being run out of Kansas in 1959, decried as a corrupt politician, his wife committed suicide, and he found himself a single parent of five, hiding out from his landlord in a Berkeley, California, ghetto. Amazingly, at that time most of his accomplishments were still ahead. After a satisfying and successful political career, in his last decades he was increasingly disenchanted with the Republican Party as it turned away from the cause of civil rights, and he briefly ran for the 1996 Republican presidential nomination to protest Bob Dole’s disavowal of affirmative action, Fletcher’s signature policy achievement.

I came across Art Fletcher while working on my dissertation—now book—on the Philadelphia Plan.1 Fletcher took over this Johnson administration program and developed it into an effective integration tool, which the Nixon administration then used for political purposes. (Fletcher would ultimately make a habit of outspoken—if friendly—opposition to the Republican presidents who employed him; soon after the first President Bush named him chairman of the United States Commission on Civil Rights, he publicly opposed the president’s initial veto of what would eventually become the Civil Rights Act of 1991.) Everywhere I turned, it seemed, I encountered this larger-than-life, blustery ex-football player who appeared to be trying to cram a lifetime of experience into every five minutes. I have found “official” Fletcher papers in the archives of the four presidents he served, and conducted hours of interviews with family members and colleagues (including Senator Dole, who remembers Fletcher fondly), but the mother lode—his personal papers—remained elusive despite several attempts to get Paul to donate them to a research library.

On my first morning in America’s sauna, Paul and I drove to his storage container. The collection was in the back of a decrepit 18-wheel trailer on the grounds of a seedy auto repair shop. We waded through weeds, and Paul removed the padlocks and opened the large double doors. There, stacked against decaying wood paneling, were about 150 boxes of varying shapes, sizes, and repair, in upward of 100-degree heat, moldering by the minute. Silverfish and larger pests occasionally crept out of the boxes, and the atmosphere had the intense smell of mold and mildew.

This was nothing like what I was accustomed to. My previous archival work had largely taken place in spacious, air-conditioned reading rooms, where the documents, thoroughly processed with finding aids, were kept by knowledgeable archivists.

Working in the trailer involved a lot of sweat. Every day was a workout, and we had to make frequent trips for bottled water. The excitement of the work often got the better of me. At one point, I had difficulty breathing and, worried that I might pass out, took a long break in my air-conditioned car.

The first thing I did was diligently number each box with a Sharpie, putting my initials next to each number so that future archivists could correctly record the transfer of documents to any new numbering system. Then Paul and I opened each box to classify each as “documents” or “not documents” (i.e., books, trophies, videocassettes, and other materials).

Once the boxes were all numbered and classified, I loaded six into my car and took them to my Airbnb room to begin digitizing them. As I usually do in archives, I set up my camera and tripod and started shooting. But after it took six hours to get through a single box, I realized that the sheer volume of this project meant months of work—and I had only two weeks. To meet my deadline, I would need to make a significant change in my method.

A stroke of luck brought strangers into my life and revolutionized the project. The Fletcher story had attracted the attention of filmmakers Lee and Leslie Sullivan from Sedona, Arizona. They and their colleague Allen Elfman, of the Sedona International Film Festival, arrived in Florida and offered to buy the film rights to my project, adding a small infusion of cash to my shoestring budget.

We used the cash to rent a high-volume scanner (Paul contributed half the cost). This large machine would speed up the digitization process tremendously. However, the prep work—removing staples and rusty paper clips, flattening crumpled pages—added time. I found myself completing about four boxes a day. Paul and I started working side by side, and Leslie Sullivan pitched in, but more strangers would have to become friends. We would need to digitize upward of 12 boxes each day in order to meet my deadline.

Paul’s friend, elementary schoolteacher Mercedes Vazquez, was the true lifesaver. She quickly became a co-leader of the project and brought in her two sons to prep documents. But the pace was still too slow. We now had the manpower, but not enough space. Set up in a bedroom in the Sullivans’ rented condo, the scanner was too often idle while we worked to prep documents. We needed to be prepping multiple boxes at a time to keep the scanner running at maximum output.

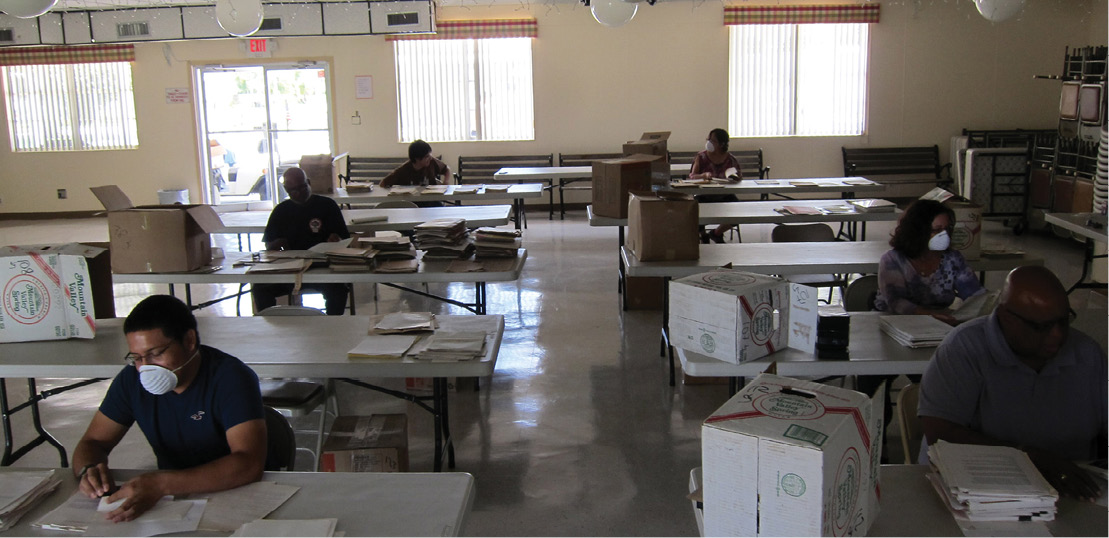

Paul came through again. He secured his neighborhood community center for the duration. We set up rows of tables as in a reading room, stacked all remaining boxes against the wall, and got to work. Mercedes and I took turns at the scanner, still using the camera/tripod to shoot fragile and oversize items. Everyone else grabbed a box and a table and started prepping documents.

Now that the scanner was working almost constantly for 12 hours a day, it started to show signs of stress. As the days passed, it started to lose features. Repairs involved long periods on the phone while remote technicians worked via an unstable Internet connection, and we soon found that we were better off adapting to the disappearing features. We added new sorting categories to the prep work, adding “paper size” and “single/double sided” to the previous categories of “scan,” “photo,” and “not needed.”

Credit: David Hamilton Golland, 2014

Temporary Reading Room, Hollywood, Florida, July 29, 2014.

These adaptations further damaged the integrity of the collection. Archivists try to maintain a collection in as close to the original condition as possible, and we were already risking the collection’s integrity with all of our other activities. The speed with which we were removing staples and the potential damage caused by the scanner would have made any archivist cringe. But by digitizing this collection, we were preserving it. The longer it remained in that trailer in Florida, the greater the potential for heat and moisture damage—or even total loss. So we cut corners with only the best of motivations. A professional judgment was needed to balance provenance, integrity, and preservation, and I made it.

The last two days were increasingly exciting as the number of unscanned boxes dwindled. “Preppers” would regularly yell “prepped!” and every time we finished digitizing a prepped box, we would call out the total number of boxes digitized that day. “Eleven!” “Twelve!” “Thirteen!” As we locked up the community center on the evening of July 30, we had 12 boxes left. We arrived the morning of the 31st in great spirits. By midafternoon we had only two boxes to go, and these were our favorite kind: filled with single-sided, 8.5 × 11, uncrumpled pages, without staples or paper clips.

And then the scanner suffered a fatal mechanical error. The rental company would repair the scanner the next day, and Paul and Mercedes would scan the remaining pages. I was disappointed to miss the completion of the project, but we had a celebratory dinner that evening with the film crew anyway, and I hit the road the next morning. Midafternoon I got a text from Paul: “Finished.”

Historians go on research trips knowing that it might be the most strenuous and time-consuming activity of the year. At home we can sleep in or work until well after midnight, but on research trips we conform to archive schedules. My work in the trailer and in the community center—prepping, shooting, and scanning documents, stacking boxes, assembling tables, and keeping the team fed and happy—was indeed the most strenuous and time-consuming activity of my year, perhaps of my career.

Back home, I have a new team working on the project: students who are cataloging the digital documents. I’m not sure what we have, but I hope it will help me write the book about Arthur Fletcher, an important if largely overlooked civil rights advocate and politician. It has already given me a new outlook on the work that we historians are fortunate to be able to do.

David Hamilton Golland is assistant professor and coordinator of history at Governors State University.

Note

1. Constructing Affirmative Action: The Struggle for Equal Employment Opportunity (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2011).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.

The American Historical Association welcomes comments in the discussion area below, at AHA Communities, and in letters to the editor. Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.

Tags: Archives Digital History

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.