Additional contributions from Timothy J. Gilfoyle, Neil Harris, D. Bradford Hunt, Patricia Mooney-Melvin, Dominic Pacyga, and Steven A. Riess.

I. A Walk along Michigan Avenue

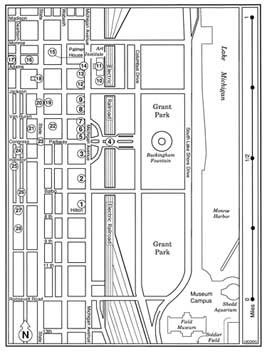

Route: north on Michigan Avenue from the Hilton Chicago Hotel to the Art Institute at Adams Street. Then west to Wabash Avenue or State Street and north a half block to the Palmer House. Cross Michigan Avenue to the sidewalk on the eastern side for a better view of the buildings.

Stop 1: Hilton Chicago and Blackstone Hotels

Two contrasting hotels stand side by side. The Blackstone appeared first, in 1908, designed by Benjamin Marshall who specialized in luxury hotels and fancy apartment buildings. His personal flamboyance was held in check by the business acumen of Timothy Blackstone, the president of the Illinois Central Railroad, who commissioned the building to be like a home away from home for wealthy patrons. The Blackstone Theater adjacent to the building was built in 1910 according to the same design, but a second tower, planned to face Wabash Avenue, was never built. The "homey" atmosphere is evident in the lobby, and the famous "smoke-filled room" of American politics that selected Warren G. Harding as the Republican nominee in 1920 is Suite 408.

The Stevens Hotel, which eventually became the Hilton Chicago, was planned for several years to be "the largest and most sumptuous hotel in the world." Completed in 1927, its exterior presents a more business-like appearance than the Blackstone.

Stop 2: Educational Institutions on the 600 Block

Columbia College and the Spertus College of Judaica take up most of the block north of the Blackstone Hotel. They have taken over space vacated by firms as the center of business shifted northward in the city and out to the suburbs. In 1908 an eight-story building was erected at 624 South Michigan to house a musical college. Seven additional stories were added in 1922 as the building was turned over to a number of business tenants. Note the lion motif at the former main entrance, a reminder of America's imperial age when the building was designed. The vacant lot next to Spertus College is used to display Leonardo Nierman's "Flame of Hope" sculpture and some street art. The Harvester Building at 600 South Michigan dates from 1907, and was later used by the Fairbanks-Morse Company. Note the elaborate cornice, which is still largely intact. Almost all buildings from this period had these cornices but few have survived Chicago's harsh winters with their alternate thawing and freezing conditions.

Stop 3: Congress Hotel

The Congress Hotel complex that occupies the entire block between Harrison Street and Congress Parkway was built in several stages. The first section, to the north, was an annex to the Auditorium Hotel across the street. Designed by Clinton J. Warren and completed in 1893 for the Columbian Exposition trade, the "Annex" set new standards for the design of hotel rooms. Note, for example, the large windows facing the park. After further additions in 1902 and 1907, the Congress became a hotel in its own right, but it has always suffered from the lack of a grand entrance and a suitable lobby. Originally the annex was connected to the Auditorium by a passageway under Congress Street.

Stop 4: Chicago's Grand Entrance

The intersection of Congress Parkway and Michigan Avenue provided a focal point for the Plan of Chicago (the pioneering and comprehensive urban development blueprint developed by Architects Daniel Hudson Burnham and Edward H. Bennett, and published in 1909—for details, see http://www.chipublib.org/004chicago/timeline/plan.html). Here the major east-west axis for the city met the major north-south street to establish a formal entrance into the city. Note the large pylons, the heroic Native American sculptures by Ivan Mestrovic (The Bowman and The Spearman, 1928), and the eagle fountains. At the end of the roadway, a block to the east, a broad stairway leads to Buckingham Fountain.

The use of Congress Parkway as a major feeder for the expressway system made it necessary to hollow out the buildings on the sides of the street to accommodate the sidewalks.

Stop 5: The Auditorium Building (Michigan and Congress)

When completed in 1889, the Auditorium Building ranked as Chicago's tallest, largest, and most complex structure. Engineer Dankmar Adler and architect Louis H. Sullivan designed a large auditorium for the core of the building, with a hotel and office space surrounding it on three sides. While the exterior load-bearing walls are stone, the interior is a massive iron frame, allowing for generous space and excellent acoustics in the expansive, 4,237-seat concert and opera hall. The building of the Civic Opera House (1929) and the Depression forced the Auditorium Building into bankruptcy in 1940; during World War II it housed the USO. In 1946, Roosevelt University purchased the entire structure for its main campus, and in 1968 the Auditorium was restored. The main lobby, 2nd floor lounge, and 10th floor library (once the hotel dining room) retain much of their original Sullivan detailing and are well worth a visit.

Stop 6. The Fine Arts Building

The Fine Arts Building, completed in 1885, sits just north of the Auditorium Building and was designed by Solon Beman, the architect of the company town of Pullman. Originally, the structure was built to house a Studebaker carriage factory. When that use became unprofitable in 1896, the building was converted to studio space for artists and renamed the Fine Arts Building. Early tenants included architect Frank Lloyd Wright, sculptor Laredo Taft, and writer Frank Baum, who wrote The Wonderful Wizard of Oz in his office here. The first American performances of George Bernard Shaw and Henrik Ibsen took place in the Fine Arts Building theater which some claimed was Chicago's equivalent of Carnegie Hall.

Stop 7: The Chicago Club

In 1885 at the same time that the Studebaker Building was under construction, Daniel Burnham and John Wellborn Root were remodeling an old two-story structure (at Michigan Avenue and Van Buren Street) into a suitable home for the expanding Art Institute. They added several stories, used a gable roof, and designed a façade featuring round arches to match those of its larger neighbor. When the Art Institute moved to its present building after the Columbian Exposition, the old structure became the Chicago Club Building. During some remodeling in 1929 the building collapsed (1929 was not a good year!). The present clubhouse (1930) tries to capture the spirit of the original design.

Stop 8: McCormick Building

This massive structure (332 South Michigan Avenue, 1910 and 1912) was built in two stages by a nephew of Cyrus Hall McCormick of reaper fame. The younger generation sought to augment its fortune in real estate and erected the south section of the building fast. After it was rented out, the northern eight bays were added to the structure, following an identical design. The huge lanterns that adorn the entrance were later additions.

Stop 9: Straus Building

This structure (310 South Michigan Avenue, 1924) differed from the McCormick Building because a change in the zoning ordinance permitted towers of additional height. The architects (Graham, Anderson, Probst, and White) took advantage of the tower to display a stepped pyramid on top with a lighted beehive at its apex. The former possibly recalled some old world precedents while the latter symbolized industry and thrift. At night, when the ornament was lit, the building as a whole resembled a lighthouse. Originally there were four beacons sending streams of light on the four compass points, but since 1954 a more sedate blue light has been used. If you look carefully you can see that the beehive is supported by four American bison, symbolizing the American interior from which the Straus investment bankers drew their strength.

The elaborate elevator doors, which celebrate the arts and sciences, are a notable interior feature to survive subsequent remodeling. After 1943 the building served as the headquarters for the Continental National Insurance Company. When the company needed additional space in 1961, an attached modern structure was built behind the landmark. Ten years later the annex was doubled in size and the Wabash Avenue complex became the new headquarters. Continental Center was then repainted, from black to red, to symbolize its new status. The old Straus Building was then restored to become Britannica Centre. Thus Chicago's first building to reach 30 stories also became a pioneer in the revitalization of South Michigan Avenue.

Stop 10: The Fountain of the Great Lakes

Based loosely on the myth of the Danaides (49 sisters condemned to carry water to fill a bottomless container in Hades as penance for killing their spouses), Lorado Taft's fountain (1913, Shepley, Rutan, and Coolidge, architects) features five maidens who move water continuously symbolizing the ceaseless movement of water through the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River to the Atlantic Ocean. The graceful maidens, each representing one of the Great Lakes, form a pyramid that is situated in a granite basin. They each hold shells and the water flows from one to another the same way in which it flows from Lake Superior—south and east toward the ocean. The fountain represents Taft's first major sculpture in Chicago and was the first public art project funded by the B.F. Ferguson Monument Fund.

Stop 11: The Art Institute of Chicago

American historians who pause in the gardens of the Art Institute may recollect that it was here, in 1893, that Frederick Jackson Turner delivered "The Significance of the Frontier in American History," possibly the most famous paper delivered at an AHA annual meeting. This building housed the expanding collections of the original Art Institute down the street (stop 7), but before the institute moved here, it was used by the World's Columbian Exposition to house many of the congresses and special meetings held in Chicago in association with the fair.

Although used in 1893, it was not until 1916 that the structure was finished. The huge bronze lions by Edward Kemeys assumed their poses in 1894 and the grand staircase was completed in 1910. Later additions and renovations have kept the building in flux ever since.

It is worthy of note that this is the only building on this tour designed by architects from outside the city. The Boston firm of Shepley, Rutan, and Coolidge was brought in to design an Italian Renaissance palace for a city seeking culture.

Stop 12: The Railway Exchange Building

The Railway Exchange, today's Santa Fe Center, on Michigan and Jackson, is a local favorite for a whole series of reasons, both aesthetic and associational. Linked to Chicago's historic past through its railroad connection and designed by one of the city's most influential and productive architectural firms, D. H. Burnham and Co., the Railway Exchange's gleaming, white-glazed terra-cotta, rippling in Chicago's occasional sunlight, makes for a powerful and dynamic presence on Michigan Avenue. Daniel Burnham moved his architectural offices to the building's top floor, and, with the panorama of the lakefront and Grant Park before them, he and his staff produced the Plan of Chicago from this location. The interior court, forming a two-story, skylit lobby, restored and renewed some years ago, is a reminder of just how intricate and dramatic these commercial spaces could be, although some think its neoclassical formality clashes with Burnham's larger design. This tension is one of the things that makes the building so exhilarating, poised between the greater austerity of the Chicago School of the 1880s and the beaux arts classicism that became a hallmark of much of the city's commercial architecture in the years around World War I.

Stop 13: Orchestra Hall

Daniel Burnham was a trustee of both the Art Institute and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. He gave his library to the former and contributed the design for a music hall for the latter. The Theodore Thomas Orchestra Hall (220 South Michigan Avenue), named for the celebrated founding conductor, was built in 1905 on the rest of the Palmer House Stable site acquired by the Burnham investment group. Note how the arched windows at the base continue a major architectural theme on South Michigan Avenue. A top-floor addition to the hall was designed by Howard Van Doren Shaw in 1908 for the Cliff Dwellers Club, a gathering of people interested in the arts.

Stop 14: Michigan Avenue and Adams Street

This lively intersection is a fit place to end a tour of the cityscape. The Art Institute with its guarding lions and the elevated structure block off sightlines to the east and west, creating an outdoor enclosure where Chicagoans feel at home. The People's Gas Building (1910) on the northwest corner is another large, ornate structure designed by the Burnham firm just after the publication of the Plan of Chicago. It perhaps presents the type of structure that Burnham thought appropriate for the new city. The decorations along the base of the building certainly reflect the motifs of the City Beautiful Movement. The southwest corner of the intersection now hosting the very serviceable Borg-Warner Building, was, it should be noted, the site of the Pullman Building from 1884 until 1956. The latter building actually faced Adams Street rather than Michigan Avenue because the stables were next door, the park largely undeveloped, and the lakefront at the time in a state of flux.

The development of this stretch of Michigan Avenue as it exists today all came after 1884 and reached its peak in the two decades following the Burnham Plan. The Borg-Warner Building, the sole representative of our generation of buildings, thus provides a measure of the distance Chicago traveled over the road of time from the early twentieth century up to the modem era.

II. A Walk along State and Dearborn Streets

The Route: Exit the Palmer House from the western doorway to reach State Street. As you leave the building, you will be facing west. Step up toward the curb and take in the cityscape at Stop 1. Then turn left and walk south on State Street. Our route will go a block out of the way after crossing Congress Parkway to catch a glimpse of Printing House Row along Dearborn Street. Go left at the foot of Dearborn Street to reach Balbo Drive and the Hilton Chicago Hotel.

Stop 16: Site of the Fair Store

The Fair store once occupied the large lot on the northwest corner of State Street and Adams Street. Later, Montgomery Ward and Company used the complex, but along with three other large department stores abandoned the Loop as merchandising shifted to suburban malls. In this case, however, not even the building was left behind, as the owners of the land hoped to erect a huge office tower. But the boom of the 1980s went bust in the 1990s.

Stop 17: Marquette Building

Holabird and Roche designed the 16-story Marquette Building (140 North Dearborn Street), named for the French Jesuit missionary, in 1895. It was one of the first structures to use steel framing, covered with brown brick and terra-cotta. It was an early example of the Chicago School of Architecture; its grid-like facade revealed the building's underlying structure. Interior lighting was enhanced by the use of "Chicago windows" with large panes of glass flanked by narrow sash windows, maximizing the amount of natural light. Its open and well-lit interior layout, built around a central light court, was very influential in the design of modern high-rise commercial structures. Even more notable was the artistic detail. The main entrance doors were paneled with ornamental bronzes depicting Marquette's life, and the marbled lobby was decorated with Tiffany mosaic panels of glass and mother of pearl, and bronze heads of native Americans, explorers, and animals and early explorers. Designated as a Chicago landmark in 1975, it was renovated and restored four years later by Holabird and Root.

Stop 18: Quincy Court

Quincy Court is the stub of a minor street that has been cut off to the west by the Dirksen Building in the Chicago Federal Center (Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, 1964). The street never proceeded east of State Street because the development of section 15, the military reservation, followed different paths than the school lands. State Street, as a section-line street, reveals these little breaks and variations in Chicago's gridiron plan. The Woolworth Store (1949) at 211 South State follows the modern style of pre-World War II days. The other buildings on both sides of the 200 block reveal the difficulties faced by architects as they tried to develop viable commercial buildings on the narrow lots in a former residential area.

A good view of the Palmer House is available from the entrance to Quincy Court. Note its formal, restrained character, the ornamentation on top, and the careful brick work with hints of Georgian classicism. The white terra-cotta used on several buildings in the 200 block contrasts with the dignified dark brick of the hotel.

Stop 19: DePaul Center

Located at 333 South State Street, the renovated building has had a long history as part of Chicago's downtown. It served originally as the home of the Rothschild Department Store. The initial "R" can be found in medallions in the gleaming terra-cotta that covers the building. The firm of A.M. Rothschild and Company differed from other State Street retailers because it began as a department store rather than a dry goods firm that simply added on other merchandise in response to shoppers' demands. As Rothschild's business expanded the company decided to erect a new structure. In 1912 the Chicago firm of Holabird and Roche designed the steel frame Chicago School building that replaced several smaller structures owned by Rothschild and Company. In 1936 Goldblatt Brothers purchased the building and it served as that firm's flagship store until the late 1980s. For most Chicagoans over the age of 40 the building remains known as the Goldblatt Building. In 1989 DePaul University purchased the structure, which earlier had been proposed as the new home for Chicago's Central Public Library. The architectural firm of Daniel P. Coffey and Associates renovated the building and today it is the centerpiece of DePaul University's Loop Campus. The award-winning conversion cost $65 million. The structure also houses the Chicago Music Mart, a retail component dedicated to music-related businesses. This retail element recalls the history of the corner of Jackson and Wabash (one block east) once known as "Music Row." As early as 1955 DePaul University acquired the Kimball Building as the first of several buildings on Music Row. In 1981 DePaul purchased the Lyon and Healy Building adding it to its downtown campus and signaling the end of Music Row.

Stop 20: State Street

"State Street, that Great Street" is no longer a mall. It has been returned to its once glorious title as Chicago's main street. The bustling street provided Chicago's major retail strip from the late 1860s until the late 1960s. Major Chicago department stores located along the street after 1867 when Potter Palmer began to develop the street. Palmer convinced Field, Leiter, and Company to come to State Street in 1868 and he opened his Palmer House in 1870. From that time on, despite the ravages of the 1871 Chicago Fire, State Street prospered as the retail and entertainment center of the quickly growing metropolis. After World War II, however, State Street, like many other downtown strips nationally, began to fade in economic importance. Suburbanization and the creation of outlying shopping malls took customers away. During the 1950s the city attempted to "modernize" the strip, erecting space age-type streetlights in 1958 that replaced the 1926 Beaux-Arts lampposts originally designed by Chicago architects Graham, Anderson, Probst, and White. Nevertheless by the late 1960s North Michigan Avenue began to replace State Street as the city's most prestigious shopping district. In 1975 the opening of Water Tower Place on North Michigan Avenue, which included a Marshall Field and Company store, seemed to guarantee the end of State Street's dominance. The city responded by creating the State Street Mall. Built at a cost of cost $17.2 million, the new pedestrian mall and transit-way (only buses were allowed) was dedicated on October 29, 1979.

The "malling" of State Street did not save the strip, but actually seemed to push it into further decline. Finally in 1995 the city began to tear up the mall and return traffic to State Street. The retail street reopened to automotive traffic on November 15, 1996. Copies of the 1926 Beaux-Arts lampposts were erected along with planters and subway entrances that recall the street's glory days (ironically, before the subway existed). Bronze plaques inserted into the reddish and gray sidewalks provide a self-guided tour of the street's many architectural landmarks including the Carson Pirie Scott Building and the 105-year-old Reliance Building reborn in 1995 as the Hotel Burnham after a $27.5 million renovation. The Harold Washington Library Center anchors State Street's southern border. New businesses have returned to the street, as have various institutions of higher learning. In 2002 State Street is enjoying a renaissance with many of its landmark buildings being restored and finding new tenants.

Stop 21: Harold Washington Library Center

It is worth spending some time at the Harold Washington Library Center because the city's most recent public building seems to sum up several themes of Chicago's development. The solid, block-like structure not only projects the city's toughness of character but also the business-like grid of its plan. The location facing Congress Street deliberately pays homage to the Burnham Plan, which called for lining this axis with impressive public buildings. The oversize ornaments on the building's exterior relate better to the cars on the expressway link than they do to the pedestrians on the sidewalk.

Once inside, however, the library patron meets friendly spaces such as small study areas cut into the walls and a glass-enclosed wintergarden on the roof. Tours of the building are offered on a regular basis.

Stop 22: Leiter Building

The long, workman-like structure (403 South State Street) that parallels the library on the other side of State Street is a study in contrasts. It seems to float above the pavement instead of reaching down to bedrock like the Thomas Beeby design.

Designed by William Le Baron Jenney, the father of the skyscraper, and built in 1891, it created vast open spaces on each floor, a construction feature unheard of at the time. The developer, Levi Z. Leiter, the former partner of Marshall Field in the department store business, wanted to keep the interior space flexible as he sought to meet the needs of future tenants.

The building was rented out in its entirety to Siegel, Cooper, and Company and functioned as a department store for almost a century, most recently as Sears, Roebuck, and Company. The flexibility that Jenney had built into the original design was then used to make an easy transition to an office building. Several governmental agencies-including a U.S. government bookstore on the first floor-currently occupy the building.

Stop 23: Congress Parkway

This stop really should be called a crossing that must be undertaken with care because the street now serves as a major feeder for Chicago's expressway system. Until the 1950s, Congress Street ended at State Street. Daniel Burnham's proposed grand boulevard, which would extend the street across the city, had to wait until the automobile took hold of the city before it was implemented.

Once on the south side of Congress Street, look back at the Leiter Building and note why it has been honored as one of the first expressions of a large commercial building as a pure geometric form. Compare the effect produced by the Harold Washington Library Center. Then walk west, cross Plymouth Court, and turn left (south) on Dearborn Street where you enter another part of the city.

Stop 24: Printing House Row

Because the railroads did not arrive in Chicago until its second generation, they had difficulty securing a right of way into the heart of the business district. A transitional area thus developed in the late 19th century between the city center and the railroad station at the foot of Dearborn Street. The printing trades soon filled this area because of the advantages of having both business clients and transportation facilities close at hand. This stretch of Dearborn Street then became known as Printing House Row.

Congress Street at the time did not extend west of State Street. Printing House Row extended north, therefore, to Van Buren Street, presenting a solid front of buildings all the way to Harrison Street. The Plan of Chicago called for cutting a wide swath through this district to extend Congress Street, a project that was implemented in the development of the city's expressway system.

By the 1970s both the railroad and the printing facilities were out-of-date and no longer needed at this location. Much of the land then reverted to residential use, its function a century earlier. New housing was constructed on the land formerly used by the railroad while many of the old printing shops were converted into apartments.

The Hyatt on Printers Row (500 South Dearborn Street) occupies two such facilities along with some new construction. The former Duplicator Building at 530 South Dearborn dates from 1886. The Morton Building, to the south, was designed in 1896 by Jenney's firm, which had done the Leiter Building just five years earlier. The industrial building is actually much more ornate than the one devoted to retailing.

The Old Franklin Building on the east side of the street (525 South Dearborn Street) dates from 1887. Note how its windows were grouped together to provide as much light as possible for the typesetters inside. The Ellsworth Building (1892) next door, a 14-story skyscraper, was one of the last structures erected by John Van Osdel who designed the Palmer House buildings in the 19th century.

Stop 25: Pontiac and Transportation Buildings

The pair of buildings south of the Hyatt Hotel provide a solid west wall for Printing House Row. Both are notable structures in their own right.

The Pontiac Building (542 South Dearborn Street), an early steel-frame structure, was designed by Holabird and Roche in 1891, the same firm that produced the Marquette Building several years later. The Pontiac uses projecting bays to increase the ventilation in the offices, but it does not use the wide windows that made the Marquette such a success. The brick work on the Pontiac seems to hide the building's steel frame, while the terra-cotta of the Marquette articulates it. The Pontiac thus is a transition design as the architects worked out the full possibilities of skyscraper architecture.

The Transportation Building runs the entire length of the 600 South Dearborn block. Dating from 1911, its 22 stories made it the tallest structure south of the Loop. As such its roof housed early towers for sending out radio signals. The name of the edifice suggests that not every building on the street was entirely devoted to printing and publishing.

Stop 26: Franklin and Donohue Buildings

The first Franklin Building proved to be such a success that the developers commissioned a second structure at 720 South Dearborn. This industrial-loft structure has reinforced floors to hold heavy printing presses. The terra-cotta ornamentation recalling the history of printing adds a decorative flair that also characterizes several of the building's neighbors. Note the gable at the top that frames a huge skylight enclosing a three-story space with glass on two of its sides as well as on top.

The Donohue Building at 711 South Dearborn Street is the oldest major building in the district, dating from 1883. The word skyscraper had just been coined to describe a 10-story building across town and the idea of an iron or steel frame to carry the weight of a tall building was not fully implemented until 1885. The Donohue Building is thus worth a second look (and special efforts to preserve it) as a part of a world that Chicago has almost lost. Behind a 1913 south annex to the Donohue Building is another treasure, the Lakeside Press Building at 731 South Plymouth Court. The architect, Howard Van Doren Shaw, creatively blended traditional approaches to ornamentation with the needs of an industrial facility. The building was erected in two stages in 1897 and 1902.

Stop 27: Dearborn Station

Since it served several eastern lines connecting to New York, the old train station at Dearborn and Polk streets became the major point of entry for the new immigrants entering Chicago. The station dates from 1885, but a fire in 1923 altered the appearance of the tower and the roof line. The structure was recycled as a neighborhood shopping center in 1983, but its great train shed has not survived.

Note how Polk Street in front of the station was enlarged to alleviate the traffic congestion generated by thousands of travelers who used the station every day. This generous space, now an anachronism, permits views toward the River City development to the west and of the Chicago Hilton to the east.

Stop 28: Dearborn Park and Return to the Hilton Chicago

At this point you can decide to return to the Hilton Chicago by walking three blocks to the east along Polk Street and Balbo Drive. Or you can linger at Printing House Row to take advantage of one of the fine restaurants in the area. (The Mexican restaurant in Dearborn Station's east wing is one of Chicago's best.) After some refreshment, an eager observer of the urban scene might enjoy walking through the newly built neighborhood called Dearborn Park that now occupies the former train yards south of the old station, before returning to the hustle and bustle of the Hilton.

Tags: Annual Meeting Annual Meeting through 2010

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.