John Hope Franklin, the most thoughtful of friends and always supportive colleague, spent a lifetime on the front lines of the struggle for justice and racial integration. He had a deep appreciation for the scholar’s responsibility in the public square.

John Hope Franklin, the most thoughtful of friends and always supportive colleague, spent a lifetime on the front lines of the struggle for justice and racial integration. He had a deep appreciation for the scholar’s responsibility in the public square.

His first foray into law and policy came when Thurgood Marshall persuaded him to write a report on higher education in Kentucky for a desegregation case the NAACP had filed. Using the report, Marshall won the case ordering the admission of Lyman Johnson to the University of Kentucky in 1949. When Marshall needed a history of the 14th amendment for the Brown v. Board of Education litigation, he naturally turned to John.

Marshall assembled a team of psychologists, political scientists, and other historians who remained on call. But John trekked up to New York from Howard University each week to spend weekends at the Legal Defense Fund offices where Marshall was always on hand. The historians’ conclusion that the amendment did not explicitly include or exclude public education removed congressional intent as a barrier to the Supreme Court decision.

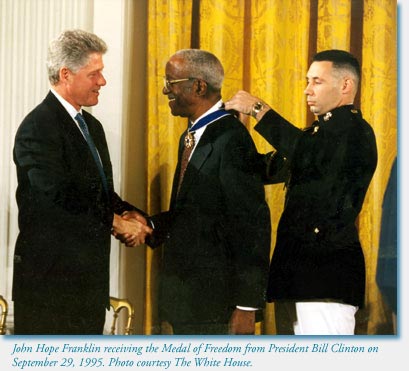

John Hope Franklin never abandoned the cause of civil rights. He remained an engaged board member of the NAACP LDF. He was among the historians gathered for the march from Selma to Montgomery. In later years, he testified against Robert Bork’s flawed interpretation of the 14th Amendment, which helped lead to the rejection of Bork’s Supreme Court nomination by the Senate. He published an op-ed piece in the New York Times on Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas’s equally flawed views. He famously chaired President Clinton’s Advisory Commission on Race (a position in which he unfortunately had to also see and deal with a series of fractious disputes, none of his making).

W.E.B. Du Bois, who, like John Hope, was a Fisk graduate, kept the pledge he made at the beginning of his career to make a name for himself as a scholar but to also “raise my race.” John succeeded him as the quintessential scholar activist—a true public intellectual. They both continued to work into their nineties, becoming more militant as they grew older. John Hope Franklin, like Du Bois, believed that the public debate was too important for scholars to remain mere onlookers.

—Mary Frances Berry is the Geraldine R. Segal Professor of American Social Thought and professor of history at the University of Pennsylvania.

Tags: In Memoriam Diversity, Equity, & Inclusion

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.