On a clear day in winter, you can see three national parks from downtown Seattle. Mount Rainier (14,410 feet), the central feature of the park that bears its name, looms above the city's skyline to the south. The Olympic Mountains, preserved within Olympic National Park, rise out of the Puget Sound to the west, and the Cascade Range to the east angles north toward Canada and the "sea of peaks" that forms the North Cascades National Park. As many have in Seattle over the past century, you may be drawn to visit the mountains, for they are all within roughly a two-hour drive of the city. Few other major urban centers can make a claim to such an abundance of wild lands within easy reach. Their proximate presence suggests that Seattle has strong ties to the natural world, but the story of Washington's National Parks also reveals that the automobile is central to understanding the meaning of national parks as wild places in the 20th century.

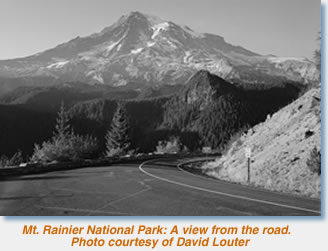

Mount Rainier National Park: View from the Road

Mount Rainier National Park: View from the Road

Created in 1899, Mount Rainier National Park was the nation's fifth national park, and Washington's first. In 1908, it became the first park to admit automobiles, altering how Americans would experience national parks and creating new expectations about how they would encounter wild landscapes. Mount Rainier National Park's biggest supporters, the residents of Seattle and Tacoma, viewed Mount Rainier as a symbol of their region's and cities' scenic beauty and a source of tourist revenue, but they also thought of parks within the context of the motor age. Cars brought the park closer to them physically and altered how they thought of it conceptually. They endorsed the use of cars in the park and viewed the development of roads for auto touring as economic and recreational enhancements.

Seattle and Tacoma residents made up the majority of the park's visitors. They believed that automobiles could be compatible with wild nature and primitive settings could be closely associated with urban centers. To contemporaries, parks like Mount Rainier were part of a greater highway geography in which national parks were connected by roads and cars and thus were extensions of daily life.

Park patrons accepted cars in parks because park roads, in the tradition of 19th-century landscape parks like Central Park in New York, appeared to harmonize with the natural world. In the early 20th century, landscape architects and engineers designed roads to conform to the landscape, to arrange scenic views and, through principles of rustic architecture, to appear as if they were anchored in the earth. The road to Paradise, a popular subalpine meadow with close views of the peak, typified this approach. Along the road, drivers entered the park through a massive log portal, wound through a dark forest, passed meadows, and gradually ascended the mountain in a series of turns that, like stanzas in a poem, revealed an unfolding panorama of glaciers, rocks, and sky. It was possible, it seemed, to reconcile machines with wild nature. (For more information, see www.nps.gov/mora.)

Olympic National Park: Wilderness with a View

By the early 1930s, wilderness advocates began to argue that no matter how appealing to the eye, the designed roads and landscapes of parks like Mount Rainier destroyed the primitive character of national parks. The creation of Olympic National Park in 1938 was a response to these shifting perceptions about the appropriate relationship between automobiles and nature in national parks. With no road running through it (Highway 101 runs around the park), Olympic was dedicated to wilderness. If Olympic National Park symbolized anything, it was the primitive, and the concept of viewing nature from the road took on a new meaning now. Located on the remote Olympic Peninsula between the Pacific Ocean and Puget Sound, the park preserved a large region (some 900,000 acres) rich in resources including ancient forests, mountains, coastline, and wildlife.

Although managing a national park as a roadless wilderness was an important change for the National Park Service, the agency never lost sight of an ideal of parks as primitive landscapes open to cars. The majority of park visitors still experienced parks from their automobiles. A signature feature of Olympic—and a key aspect of preserving its "true wilderness"—became the Hurricane Ridge Road. The road, completed in the late 1950s, connected the town of Port Angeles to a high vantage point on the edge of the park, offering panoramic views of the mountainous interior, views considered the best in the park. Although more modern in its design than Mount Rainier's roads, the Hurricane Ridge Road conformed to topography and to the original notion of wilderness in a national park as something viewed from a road and through a windshield. At the same time, Park Service leaders regarded the road as an innovative way to address the issue of autos and wilderness in national parks. It created the illusion that cars could enter national parks without defiling them. (For more information see www.nps.gov/olym.)

North Cascades National Park: A Road Runs through It

In 1968, Congress created North Cascades National Park, a victory of the postwar environmental movement that protected one of the last large wilderness areas (684,000 acres) left in the contiguous United States. It also seemed to be the final stage in literally pushing cars to the margins of park management. But Congress had other things in mind. It created a "park complex" of national park units and recreation areas that essentially tried to please everyone. The legislation prohibited roads and cars in the new park, while allowing them and other traditional park uses in the adjoining recreation areas and calling them "wilderness thresholds."

Initially, the Park Service proposed alternative means of transportation, like tramways, so that visitors could actually see the park's signature feature of serrated peaks high above the highway corridor. Although tramways were an imaginative solution, they were highly problematic to build and maintain, and so did not replace cars as the main mode of travel in the park. Instead, the Park Service provided visitors with what they had come to consider a typical park experience: driving through an otherwise wild and impenetrable mountain country. (In this case, travel in the "park" was really in Ross Lake National Recreation Area over Highway 20.) One of the main differences, however, between the experience of motoring in North Cascades and that of driving through older parks like Mount Rainier and even more recent additions like Olympic was that motorists never gained a sense of arrival; there were no massive log gates to pass through or any grand views awaiting them. In fact, visitors never arrived in the park itself. Rather, motorists could learn about the wilderness few would ever see beyond the highway by reading roadside interpretive displays and watching a film at the park visitor center. (For more information, see www.nps.gov/noca.)

Road Trip: A City and Its Parks

Over the 20th century, cars, roads, and wilderness have evolved together in national parks, and thus are deeply entwined with the ways in which we experience parks. But this story also reminds us that journeys to and experiences with national parks begin and end in cities like Seattle. Whether or not you venture out to Mount Rainier, Olympic, or North Cascades National Parks this winter, they are part not only of Seattle, but also of the larger landscape around the city, and therefore, around you.

— David Louter directs the history program for the National Park Service's Pacific West Region. His book, Windshield Wilderness: Cars, Roads and Nature in National Parks, is forthcoming from the University of Washington Press.

Tags: Annual Meeting Annual Meeting through 2010

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.