Thomas D. Clark, Distinguished Professor Emeritus, University of Kentucky, died after a short illness on June 28, 2005. An extraordinary man, he was an inspirational teacher, a scholar who published more than 30 books on Kentucky, southern, and frontier topics, an academic citizen who led colleagues not just on his campus but also in major professional societies, a dedicated collector and preservationist of primary material, a conservationist who both wrote about and practiced his love for forests, and an indefatigable and influential lobbyist in Kentucky for history, archives, and public education. Shortly before his death, he completed his memoir and his rich life is certainly worth remembering.

Thomas D. Clark, Distinguished Professor Emeritus, University of Kentucky, died after a short illness on June 28, 2005. An extraordinary man, he was an inspirational teacher, a scholar who published more than 30 books on Kentucky, southern, and frontier topics, an academic citizen who led colleagues not just on his campus but also in major professional societies, a dedicated collector and preservationist of primary material, a conservationist who both wrote about and practiced his love for forests, and an indefatigable and influential lobbyist in Kentucky for history, archives, and public education. Shortly before his death, he completed his memoir and his rich life is certainly worth remembering.

He was born July 14, 1903, in a log cabin on a farm near Louisville, Mississippi. The world he saw as a child was rural, almost frontier. The past was real for this boy who knew Confederate veterans, former slaves, and Choctaw Indians. After completing the seventh grade, he worked for several years on his father’s farm, a sawmill, and finally on a dredge boat clearing a large swamp. At 18, he went to high school and graduated four years later. He earned enough money cultivating 10 acres of cotton to go to the University of Mississippi. Under the tutelage of Charles S. Sydnor, he realized that he wanted to do history and he secured a graduate fellowship at the University of Kentucky. He completed his master’s degree in a year and then earned his PhD under William K. Boyd at Duke University three years later. His first two books, monographs about early southern railroads, came out of his graduate work.

In 1931, he joined the faculty at the University of Kentucky. Clark developed a lecture style that over the years informed and entertained an estimated 25,000 students with his broad knowledge and personal experience spiced with storytelling and humor. The university president expected Clark to collect material to make the library a graduate research source. Clark attacked this mission energetically, going about the state by auto and in at least one case on a mule, to secure the personal letters, business records, and newspapers which students still research. In the course of these journeys, which he continued for more than 70 years, he built a huge network of friends and acquaintances.

As a historian he always put people first. He clearly saw their limitations and weaknesses but he admired their courage, compassion, and humor. He once wrote: "The most distinguished hero America ever produced . . . was the common man whose victories were won at the handles of the plow and the ax." In his books and in his lectures, he dealt with the personalities and the experiences of frontiersmen, farmers, country storekeepers, and smalltown newspaper editors as well as the major economic and political problems with which they had to cope. When you listened to or read what he had to say, you sensed the hard work of plowing all day with a mule, of hearing hellfire and damnation preachers, and those storytellers who gathered around potbellied stoves in country stores. He once vividly illustrated the tension between the small store owners and the tenant farmers who were ever in their debt by showing a class the yellowed crop lien notes that he secured in his research for Pills, Petticoats, and Plows: The Southern Country Store (1944) and which he deposited along with the huge collection of other store records he collected in the University of Kentucky library.

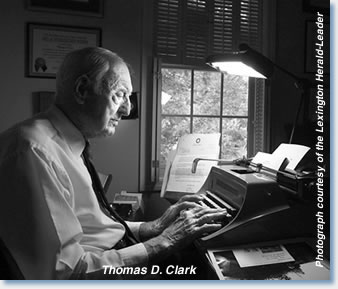

Others among his more than 30 books which came from his portable typewriter include A History of Kentucky (1937), "The Kentucky" in The American River Series (1942), Kentucky: Land of Contrasts (1968), The Southern Country Editor (1948), The Greening of the South: The Recovery of Land and Forest (1984), The Rampaging Frontier: Manners and Humors of Pioneer Days in the South and Middle West (1948), a three-volume history of Indiana University, and assorted monographs, bibliographies, edited works, and textbooks. All demonstrate his interest in people and his frank appraisal of events that he never romanticized, and were written with clarity and wit.

He was a member of the faculty at the University of Kentucky from 1931 to 1968 and chaired the department from 1942 to 1965. Among his other contributions to this university he was the leading force in establishing the University Press of Kentucky. Throughout his career, he visited at other universities in the states and abroad including Harvard, Wisconsin, North Carolina, the University of Vienna, and Indiana University, where he taught from 1968 to 1973. He was also active in organizations, serving as president of the Southern Historical Association (1947) and as editor of the Journal of Southern History (1949–52). Later he was president of the Organization of American Historians (1956–57) and was executive secretary (1970–73). He received the AHA’s Award for Scholarly Distinction in 2004.

In addition to developing the research collection at the University of Kentucky, he saved the state archives, served 44 years on the Archives Commission, and led the movement to erect an archives building. In his 90s, he fought hard to obtain a suitable building for the Kentucky Historical Society. In addition to writing about the preservation of forests, he never tired of visiting and supervising his two tree farms.

After his retirement from academe, he continued to publish books, lobby for an equitable public education system, and various local and state history related issues. He continued his speaking schedule throughout the state past his century mark and never stopped collecting research material. As Wendell Berry wrote: "He was put here with a long spring tightly wound." A few weeks after his 100th birthday, I encountered him in a Lexington book store on the hottest day of the year. He excitedly told me that he had spent the morning searching an ante-bellum mansion including the attic and had located a treasure trove of papers which he deposited in the Kentucky Historical Society.

He was survived by his wife Loretta Gilliam, a son Bennett, a daughter Elizabeth, three grandchildren, and five great-grandchildren. His first wife, Elizabeth Turner, died in 1995. He was also mourned by thousands of Kentuckians who appreciated what he had done for them and their state.

—Edward M. Coffman

University of Wisconsin at Madison

Tags: In Memoriam

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.