The Art of History

The Human Rights Historian and the Trafficked Child: Writing the History of Mass Violence and Individual Trauma

The eyes of a young woman, stolen from her family when she was six years old and kept as a slave for a decade, stare back at me from a League of Nations' document and across the elapse of 90 years.1 They belong to Loutfiyé Bilemdjian from the city of Ayntab, now Gaziantep, in southern Turkey. Hers is the 1,010th entry in a collection of notebooks that record the narratives of young survivors of the 1915 genocide of the Ottoman Armenians as they entered the care of the league's Rescue Home in Aleppo, Syria. In addition to the narrative, each page includes a photograph taken at the time of admission and as much biographical information as the young person could remember-parent's name, place, and date of birth.

The eyes of a young woman, stolen from her family when she was six years old and kept as a slave for a decade, stare back at me from a League of Nations' document and across the elapse of 90 years.1 They belong to Loutfiyé Bilemdjian from the city of Ayntab, now Gaziantep, in southern Turkey. Hers is the 1,010th entry in a collection of notebooks that record the narratives of young survivors of the 1915 genocide of the Ottoman Armenians as they entered the care of the league's Rescue Home in Aleppo, Syria. In addition to the narrative, each page includes a photograph taken at the time of admission and as much biographical information as the young person could remember-parent's name, place, and date of birth.

As Loutfiyé told a league relief worker, at the onset of the genocide, she and her family had been forcibly displaced to upper Mesopotamia, where they were set upon by Ottoman irregular soldiers. She witnessed the killing of her mother, father, and one of her brothers. A soldier took her as booty and sold her to someone, who then resold her to a wealthy man named Mahmud Pasha. He sent her to his house, where she remained for 11 years. In 1926, she escaped across what had become the international border between Syria and Turkey and reached Aleppo, where she found one of her surviving brothers.

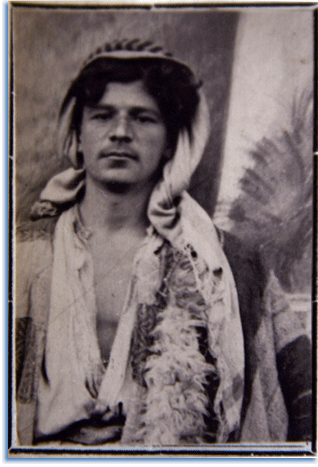

Elements of her story are similar to entry number 961, which tells the story of Zabel, the daughter of Bedros from Arapgır, a village known for its wine grapes and woven textiles. She was sent into the Syrian desert in 1915 with her mother, five sisters, and a brother. Along with other girls from her village, she was gathered by Ottoman gendarmes and sold. In the elliptical language of the interwar period, her purchaser "married her." She was 7 or 8 years old at the time. After 11 years she learned that other Armenians had survived. She escaped and made her way to Aleppo where she was reunited with family. Her story is not unlike that of number 209, Khachadour Beroian, from the city of Kharpert, now Elazığ in Turkey, whose picture shows him wearing a kaffiyya and a wool-lined caba' coat-clothes he wore as an unpaid agricultural laborer in eastern Syria before he ran away from the farm where he'd been forced to work for 9 years. He was around 12 years old when his father, Avedis, was killed at the beginning of the genocide. Like other orphaned children in his city, he had been rounded up and sent to Syria in a deportation caravan.

Over the course of two summer days, I sat in the reading room of the league's archive in what is now the UN's Geneva headquarters, and read these stories, one by one, hour after hour. Each record told a consistent story of survival in the face of extrajudicial murder, forced migration, enslavement, or sexual violence.

The stories tore at me.

Perhaps it was because I knew people who could have been their descendants; their names, their faces, their places of origin were all familiar. I knew, as a historian of the period, that these were the few who by force of will or circumstance (or both) had escaped. Hundreds of thousands of children were killed during the genocide, and, at the time of the Rescue Home's operation, tens of thousands of Armenian young people were still living in slavery.

The stories stayed in my mind even as I left the archive and walked to my apartment, passing under the canopy of the most magnificent Cedar of Lebanon I had ever seen. That night I awoke screaming from a dream the details of which I'm glad I couldn't recall.

Making Meaning of Trauma

What burdens do such stories of individual trauma and survival place on the historian? Trying to answer this question is important, inasmuch as the spoken, written, and forensic texts of witness, memory, and testimony form the building blocks of human rights history. But the question can also be answered by thinking about why the league's administrators recorded and preserved these stories. Clearly, the biographical data and pictures were a tool for family reunification. Sometimes, a page's overleaf has an entry on the placement of the young person with family nearby, or, like Khachadour, emigration to join his brother in America. Combining photographs and individual stories gave human meaning to the raw numbers needed by the league's bureaucracy; it was calculated to generate funding or support from representatives of member states and secretariat officials.

A league-produced reenactment of a young woman entering the Rescue House from a 1926 film-itself a remarkable and evocative piece of evidence-shows her telling her story to a league employee, who then translated and wrote it down.2 The field workers believed that the act of telling one's life story at entry helped the individual mark that moment as a rupture between the time she spent as a trafficked child, unconsenting wife, or domestic slave, and a new life as a member of a natal community. Putting the story-her history-down on paper acknowledged the past in a way that could help her make a dignified return to something approaching a normal life. The break from the past was reinforced as the young people shed the clothes they wore upon entry and were given Westernstyle dresses or pants and had their hair cut.

A league-produced reenactment of a young woman entering the Rescue House from a 1926 film-itself a remarkable and evocative piece of evidence-shows her telling her story to a league employee, who then translated and wrote it down.2 The field workers believed that the act of telling one's life story at entry helped the individual mark that moment as a rupture between the time she spent as a trafficked child, unconsenting wife, or domestic slave, and a new life as a member of a natal community. Putting the story-her history-down on paper acknowledged the past in a way that could help her make a dignified return to something approaching a normal life. The break from the past was reinforced as the young people shed the clothes they wore upon entry and were given Westernstyle dresses or pants and had their hair cut.

Bringing human meaning to "the number" is among the central challenges of writing about genocide or other kinds of mass human rights abuses like state violence, ethnic cleansing, and slavery. As historians, we need to be able to write about the anonymous scope and remorseless uniformity of genocide-to explain its modernity, its political and social importance, and the intent of perpetrators. But as the numbers mount they become numbing and mute, and the historical experience of genocide is flattened.

A focus on the individual behind the cold numbers of dead or trafficked children can obscure the larger concepts and even leave the historian vulnerable to claims that his history is merely anecdotal or unrepresentative. We have, nonetheless, a responsibility to listen when we can to the voices of those victimized by human rights abuse and to disentangle those voices from dominant narratives of powerful institutions and nation states-especially in those very rare instances when we hear children's voices.

The Unbearable and the Historian's Humanity

To achieve balance between these two ways of writing the history of episodes like the Armenian Genocide, the historian should embrace his emotional responses, like the ones I had at the archive, to unleash as a tool of method his empathetic imagination. This way of imagining is central to what makes our discipline humane and helps the historian retain the humanity of his work (and himself) when confronted with hate, violence, and inhumanity. Moreover, it can bring history and the historian into broader conversations about justice, acknowledgement, and reconciliation, which is one of the promises of human rights history.

In the years since I returned from the archive, those narratives have shaped the way I've written about humanitarianism and human rights in the Middle East.3 As Syria has again become a killing field, the stories helped me think about what it means to be a young person displaced by war-and led me to a refugee camp in the Jordanian desert to research and advocate for displaced Syrian university students.4

Even now, when I tell the story of the children in the notebooks to my students or, recently, to a group of high school social studies teachers preparing a curriculum on genocide, I can still feel a burning ember of the sadness I experienced in the archive.

-Keith David Watenpaugh is a historian of the modern Middle East and director of the University of California, Davis, Human Rights Initiative. His work has appeared in the American Historical Review, International Journal of Middle East Studies, Social History, Journal of Human Rights, and Humanity and has been translated into Arabic, Armenian, German, Persian, and Turkish. He is the author of Being Modern in the Middle East, and the forthcoming Bread from Stones: The Middle East and the Making of Modern Humanitarianism.

Notes

1. Archives of the League of Nations, United Nations Organization, Geneva, Records of the Nansen International Refugee Office, 1920-47, "Registers of Inmates of the Armenian Orphanage in Aleppo," 1922-30, 4 vols.

2. Karen Jeppe, Danish Film Institute, director unknown (1926).

3. See my article, "The League of Nations' Rescue of Armenian Genocide Survivors and the Making of Modern Humanitarianism, 1920-1927," AHR 115, no. 5 (December 2010): 1315-39.

4. K. D. Watenpaugh, A. E. Fricke, et al., "Uncounted and Unacknowledged: Syria's Refugee University Students and Academics in Jordan," a joint publication of the University of California, Davis, Human Rights Initiative and the Institute of International Education (April 2013).

Tags: Profession Resources for Faculty Thematic

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.