Making Space for Shi'ism in Afghanistan's Public Sphere and State Structure

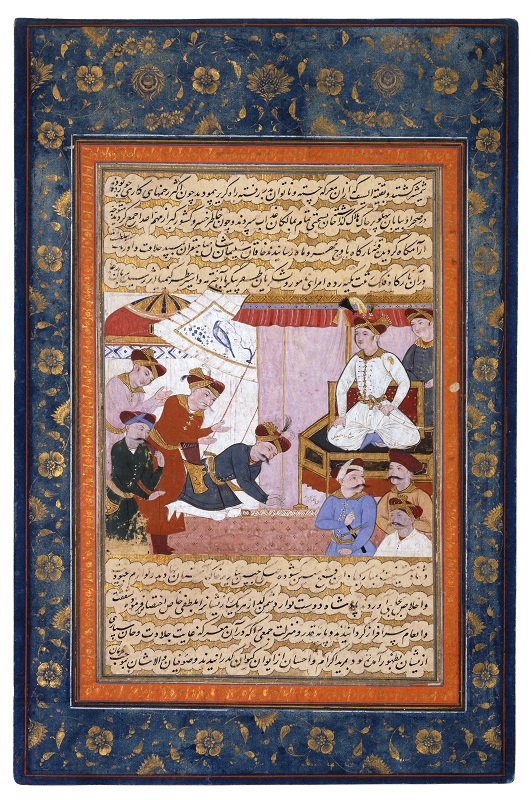

In Kabul, Afghanistan, a city that is over 1,500 years old, arguably the most famous landmark is the grave of the founder of the Mughal Empire (1526–1857), Zahir al-Din Muhammad Babur (c. 1483–1530). Unveiled in 2008 after a six-year renovation effort, the grave and garden complex were restored by the Shi’a-led Agha Khan Development Network (AKDN), even though Babur was not Shi’i. That the organization responsible for the restoration of the grave is a Shi’i organization would have been unusual before 2001, but no longer is. In the last 14 years, two Shi’i groups, the Hazara and the Qizilbash, have claimed a greater presence in the public life of Afghanistan, the majority of whose citizens are Sunni.

Government recognition of Shi’ism has led to greater Shi’i representation on the National Council of Ulema (Islamic religious scholars), and the formation of a distinct bureaucracy for Husseiniyyas, or shrines where the Shi’i Imam Hussein is ritually venerated. New mosques and schools have also been built for the Shi’a. Both mass media and social media now target Shi’i audiences as well as Sunni audiences. In the aspiring democratic context of post-2001 Afghanistan, the Hazara and Qizilbash have entered the public sphere, including new bureaucratic spaces designed to accommodate and recognize Shi’ism.

Additionally, new construction and renovation of historic landmarks such as the grave of Babur also represent greater public participation of the Shi’a in Afghanistan. This is largely a product of two factors: international capital and human resources tied to multiple singular state policies toward Afghanistan, and the thousands of nongovernmental organizations in the country. As an example, the AKDN is an international network of development agencies funded by the spiritual leader of the globally dispersed Sevener community of Shi’a Isma’ili Muslims, Shah Karim al-Husseini (b. 1936), who now carries the hereditary title Agha Khan. Another Shi’te external force in Afghanistan has been the Iranian government, which follows the Imami, or “Twelver,” branch of Shi’ism. It has been a primary external state sponsor of mosques, schools, computer labs, libraries, hospitals, and other new construction projects in Afghanistan.

The local meanings of these sites are shifting the political landscape of Afghanistan. Shi’i and Sunni Afghans alike use the new historical layer of physical structures in place thanks to AKDN, the Iranian government, and other international donors. The spaces have been integrated into networks of local oral and technology-based communications not only through the donation, permission acquisition, and construction phases, but also, and most significantly, in the course of daily usage.

As the public spaces have changed, the status of the Hazara has as well. Large numbers of this Turko-Mongolian population, historically concentrated in the Bamiyan, were enslaved in Kabul in the late 19th century. A much smaller number of Hazara intellectuals and scholars entered the state bureaucracy through various channels; the most significant was Faiz Muhammad Katib Hazara, who wrote the official state history, Seraj al-Tawarikh, or Lantern of Histories (1913–15). Later, 20th-century visitors to Afghanistan regularly noted the presence of Hazaras as domestic and menial working-class laborers.

The Qizilbash also gained more rights in post-2001 Afghanistan. This Persianized Turkish community has a long history of service in the Shi’i Safavid Empire in Iran (1501–1722). They were initially a tribal military force and later literate bureaucratic elites. Large numbers of Qizilbash were relocated to Qandahar and Kabul by the post-Safavid conqueror Nadir Shah Afshar. This massive relocation of the Qizilbash took place in the context of Afshar’s 1739 invasion of Delhi, which hastened the end of Mughal rule and brought on the rise of British hegemony in South Asia. Subsequently, the Qizilbash were integrated into the administrative structure of the early Afghan state under its first rulers, Ahmad Shah and Timur Shah Durrani (combined rule 1747–93). They also served as primary local allies of the British during the first colonial invasion and occupation of the country (1839–42). By the early 20th century, their prominence in the state bureaucracy and emerging public intelligentsia was such that the Qizilbash district of Kabul, Chendawul, became locally known as the “Oxford of Afghanistan.” Since 2006, multiple historic commercial and residential structures in a core neighborhood of Chendawul, Murad Khani, have been and are still undergoing extensive renovation through a joint initiative of Hamid Karzai and Prince Charles, using the British Royal Charity Turquoise Mountain Foundation with funding from multiple sources, including the AKDN.

The Qizilbash also gained more rights in post-2001 Afghanistan. This Persianized Turkish community has a long history of service in the Shi’i Safavid Empire in Iran (1501–1722). They were initially a tribal military force and later literate bureaucratic elites. Large numbers of Qizilbash were relocated to Qandahar and Kabul by the post-Safavid conqueror Nadir Shah Afshar. This massive relocation of the Qizilbash took place in the context of Afshar’s 1739 invasion of Delhi, which hastened the end of Mughal rule and brought on the rise of British hegemony in South Asia. Subsequently, the Qizilbash were integrated into the administrative structure of the early Afghan state under its first rulers, Ahmad Shah and Timur Shah Durrani (combined rule 1747–93). They also served as primary local allies of the British during the first colonial invasion and occupation of the country (1839–42). By the early 20th century, their prominence in the state bureaucracy and emerging public intelligentsia was such that the Qizilbash district of Kabul, Chendawul, became locally known as the “Oxford of Afghanistan.” Since 2006, multiple historic commercial and residential structures in a core neighborhood of Chendawul, Murad Khani, have been and are still undergoing extensive renovation through a joint initiative of Hamid Karzai and Prince Charles, using the British Royal Charity Turquoise Mountain Foundation with funding from multiple sources, including the AKDN.

Despite the power the Qizilbash wielded within the state structure and among the intelligentsia since the Afghan polity took shape out of the demise of the Safavid Empire, they did not begin to confidently advertise and stake political claim to their Shi’i identity until the 21st century. For the Hazara, who have historically occupied a far lower class position, this public and political emergence is even more dramatic. The current political activism of Afghan Shi’i communities stands in stark contrast to their pre-2001 generalized public silence, which resembled a mild permutation of taqiyya, or dissimulation, regarding their Shi’ism.

The recent public embrace of a formerly much more domesticated religious identity has transpired in a political economy organized around extensive foreign state aid and NGO development investment, and in a society experiencing a democratic transition while under international military occupation. The surge of Shi’ism in post-2001 Afghanistan has politically bridged contrasting class histories of the Hazara and Qizilbash, and it has taken place within a growing technology-based public sphere overlain upon a resilient kin-centered oral culture.

Shah Mahmoud Hanifi is a professor of history at James Madison University, where he teaches courses on the Middle East and South Asia. His publications on the history of Afghanistan address issues including colonial political economy, migration, Orientalism, and the Pashto language.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.

The American Historical Association welcomes comments in the discussion area below, at AHA Communities, and in letters to the editor. Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.

Tags: Middle East Religious History

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.