Current Events in Historical Context , Perspectives Daily

Named for the Enemy

The US Army’s Confederate Problem

As a newly commissioned second lieutenant, I reported to my first duty station at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, named for Braxton Bragg, one of 10 army posts that honor Confederate officers. The 10 honorees are a mishmash of middling tacticians, pro-slavery advocates, virulent postwar racists, and even a war criminal.

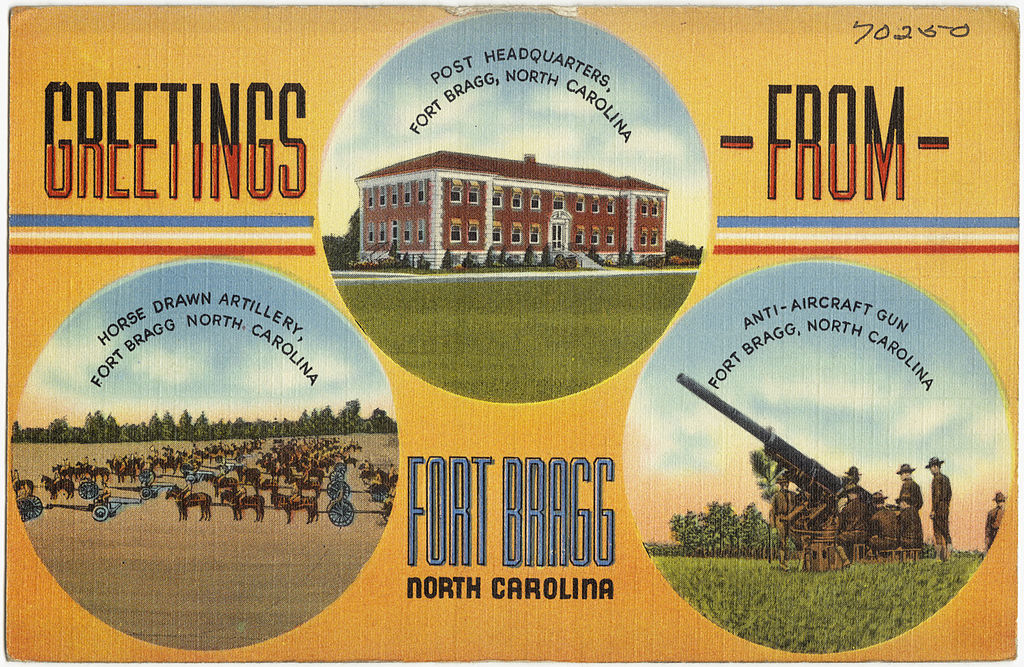

A 1930 postcard depicts Fort Bragg, North Carolina, named after Confederate officer Braxton Bragg. Century Sales Co./Boston Public Library/Digital Commonwealth

As monuments tumble across the country, the US Army’s memorialization of Confederates has come under increasing scrutiny. While Secretary of Defense Mark Esper recently banned the Confederate battle flag, the larger question remains: Why would the US Army ever honor the enemy? Robert E. Lee, for instance, has a post named after him in Virginia, a barracks at West Point, and a road at Fort Hamilton in Brooklyn, New York. Going further back, the army named a tank after him and the navy a ship. There was even a Lee Kaserne in Germany.

Yet Lee committed treason and was responsible for the deaths of more US Army soldiers than any other enemy general, ever. Despite serving in the US Army for over 30 years, he abrogated his oath and fought to destroy the United States to create a new nation dedicated to human enslavement.

In the 19th century, US Army officers would have agreed that Lee and his comrades were traitors. As a West Point graduate wrote in 1864 about army officers who chose to fight against the United States, “Treason is Treason.” The founder of West Point’s alumni organization said after the war that Confederate graduates “forgot the flag … to follow false gods.”

Monuments, however, tell us more about who erected them than the actual figure memorialized. Confederate monuments in the South served to reinforce white supremacy, much like lynching and legalized segregation. The army honored Confederates to support white supremacy as well.

The army honored Confederates to support white supremacy.

During World War I, the War Department named five posts after Confederates that survive today. Before this period, local and then regional commanders named posts. During the war, when the army went from 100,000 to 4 million troops in 18 months, the War Department took over the naming, eager not to offend “local sensibilities.” Of course, this meant white sensibilities because Black Americans had no input at the time.

For example, Fort Benning in Georgia honors Henry Benning, who advocated dissolution of the Union to protect slavery as early as 1849. He never served in the US Army. While a competent brigade commander, Benning never rose to high rank in the Confederate army. He was, however, a local favorite of the United Daughters of the Confederacy in 1918.

John Brown Gordon, namesake of Georgia’s Fort Gordon, never served in Army blue either, although he was a superb tactician. After the war, he gave a speech to the Black people of Charleston promising that if they demanded political equality, Gordon would lead a race war and “exterminate” them. Gordon also led the Ku Klux Klan in Georgia. The Gordon chapter of the Sons of Confederate Veterans wrote a letter of appreciation to the War Department after the naming. Camp Beauregard in Louisiana, Fort Lee in Virginia, and Fort Bragg also received their names during this period.

The US Army required little prodding to honor Confederates because of its own white supremacist leanings. The commander of American troops in France during World War I, John J. Pershing, wrote about how to treat segregated Black soldiers, “We must not eat with them, must not shake hands with them, (or) seek to talk to them outside the requirements of military service.” Pershing sent the segregated 93rd Division, which included the famed Harlem Hellfighters, to the French Army. The 93rd was the only American unit to wear French uniforms.

During the interwar era, the army wrote a series of annual reports on the issue of Black manpower for the next war. Their conclusions contributed to the army’s segregation policies during World War II. In 1932, army officers wrote that, “The Negro is lower on the scale of evolutionary development than the white.” Honoring Confederates reinforced the military’s white supremacist doctrine.

During World War II, five more army posts that survive today were named for Confederate officers. The names selected by the War Department, in deference to “local sensibilities,” reflect the army’s own racism combined with the power of white southern segregationist politicians. The South remained a one-party racial police state.

The Department of Defense will need to set up a task force to find Confederate memorials and either remove or rename them.

The Confederates honored in this era include Leonidas Polk, widely considered one of the worst commanders on either side. George Pickett fled to Canada after the war because he feared prosecution for a war crime: in 1864, he ordered the execution of 22 captured US soldiers as deserters because they had previously served in Confederate gray. John Bell Hood impaled his army on the US defenses in Atlanta and Nashville, leading to his epic defeat. The War Department also named Fort Rucker in Alabama and Fort A.P. Hill in Virginia during this period.

One famed Confederate commander received no recognition anywhere in the South. James Longstreet was arguably Lee’s best corps commander. After the war, however, he led a biracial militia against white supremacist terrorists in New Orleans. White Southerners called him a scalawag and prevented any memorial to the “race traitor.”

The army started honoring Confederates in the early 20th century and never stopped. The army’s flagship institution, West Point, honors Robert E. Lee with many different memorials, including a barracks. Most Lee memorials came about in the 1930s, 1950s, and early 1970s. Each of those periods saw an increase in racial integration. Confederate memorialization served as a way to buttress white supremacy and to protest equal rights. For instance, a Lee portrait in Confederate gray appeared in 1952 as a reaction to President Harry S. Truman’s order integrating the military. Prints created for the Army War College graduating classes featured pro-Confederate depictions through the 1990s. Almost inexplicably, West Point created memorials to Robert E. Lee in 2001 and 2002 as well.

Finding the countless memorials that honor Confederates across hundreds of US military bases will be no small task. The Department of Defense will need to set up a task force to find Confederate memorials and either remove or rename them.

The military has perhaps the most diverse workforce in the country. That is something to be proud of. Yet we must ensure that no one who volunteers to protect America works in a place named for someone who committed treason to protect slavery. Changing who we honor will not end racism in one fell swoop, but it’s not a bad place to start.

Ty Seidule is professor emeritus of history at West Point and a retired US Army brigadier general. He is the Chamberlain Fellow at Hamilton College. He tweets @Ty_Seidule.

Tags: Current Events in Historical Context Perspectives Daily North America Public History

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.

The American Historical Association welcomes comments in the discussion area below, at AHA Communities, and in letters to the editor. Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.