Presidential Address

In Memoriam

From the American Historical Review 77:3 (June 1972)

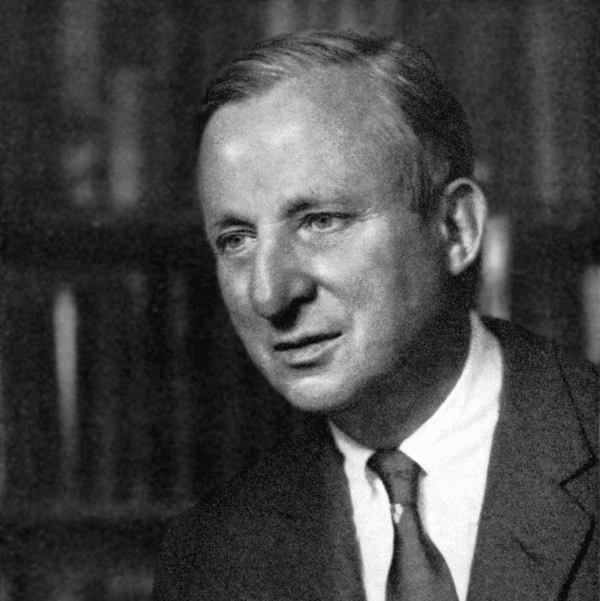

Allan Nevins (May 20, 1890–March 5, 1971), former president of the American Historical Association, died on March 5, 1971, after a varied and distinguished career of some sixty years in journalism, teaching, writing, scholarship, and academic and public service. Born May 20, 1890, on a farm outside Camp Point, Illinois, of Scottish and German forebears, Allan Nevins learned early the cardinal virtues of duty, industry, thrift, perseverance, and probity-qualities he displayed in exemplary form the rest of his life. In 1908 he entered the University of Illinois where he studied English literature and edited the college paper. He stayed on for a year after graduation to study under the brilliant Stuart Sherman and to write the first of his many books, a biography of Robert Rogers. Professor Sherman recommended the young literary critic to friends in New York City; in 1914 Nevins moved to that city, which remained thereafter his spiritual and intellectual home, and took a job as editorial writer on the Evening Post—whose history he promptly wrote. He was now fairly launched on that editorial career which was to command his lifelong allegiance, serving successively as editor on the Post, literary editor on the New York Sun, and editorial writer under Walter Lippmann on the Morning World. Nevins’s abiding interest in journalism was attested by his history of the Post, a collection of American Press Opinion from Washington to Coolidge (1928), several volumes of collected editorials by Walter Lippmann, and contributions to the Dictionary of American Biography on newspapermen and journalists, which together constitute a compendious volume. Somehow amid the exacting demands of editorial work Nevins found time to produce, in 1924, a history of the American States during and after the American Revolution, which was awarded the first of many prizes he was to receive in his Jong literary life and which remained, for almost half a century, a standard and almost a classic work in its field. Next year came the first of several versions of a biography of John C. Fremont, and in 1927 he wrote a volume in the new History of Social Life series, The Emergence of Modern America, which foreshadowed a lifelong interest in the Reconstruction era of American history.

Now fully—though not exclusively—committed to a life of scholarship, editor Nevins became, in 1927, Professor Nevins of Cornell University. Within one year, however, he had returned to New York City to join the faculty of Columbia University, an institution to which he was married and faithful for the rest of his long life.

Professor Nevins was now fairly launched on what proved to be the most productive scholarly and teaching career of any American historian, for none other of this century produced so many major books and so many major students and disciples as this unassuming scholar who was himself innocent of any academic study of history and who so conspicuously lacked the imprimatur of the PhD. Now that he could devote full time to scholarship, Nevins turned his cascading energies to the rewriting of much of American history; what was perhaps most remarkable is that he managed to write equally well for a scholarly and a popular audience; his scholarly works were written in vigorous graceful prose and his popular articles, essays, and reviews with a scrupulous regard to scholarly standards. He did not confine himself to any one specialty or area of history but was equally at home in-and productive in-biography and political, diplomatic, military, economic, social, and cultural history. His study of Fremont was followed by major biographies of Henry White (1930), Grover Cleveland (1932), Abram Hewitt (1933), Hamilton Fish (1936), and Herbert Lehman (1963). Three biographical studies proclaimed Mr. Nevins’s abiding interest in the history of business—a two-volume biography of John D. Rockefeller (1940), which was in effect a history of the Standard Oil Company and the Rockefeller Foundation; an essay (written with Jeanette Mirsky) on The World of Eli Whitney (1952); and three volumes (written with Frank E. Hill) on Henry Ford: the Time, the Man, the Company (1954–63), a full-scale history of the Ford Motor Company and even of the automobile industry in America. Two volumes in the new Yale Chronicles of America series—in addition to innumerable articles—attested a lifelong concern with foreign policy. The Gateway to History (1938), designed to invite amateurs as well as to instruct professionals, remains perhaps the most luminous introduction to the study of historiography; and a small study, State Universities and Democracy (1962), managed to say something original about American higher education.

In 1945 Professor Nevins decided to concentrate his major energies—for he could never resist the temptation of forays into other interesting fields—on a rewriting of James Ford Rhodes’s history of the United States in the Civil War era. To this work, which he planned to span a period of roughly thirty years and which he expected would require twelve volumes, he gave the felicitous name The Ordeal of the Union (1947–71). He lived to complete eight of the volumes, carrying the story from the close of the Mexican War to Appomattox. The Ordeal of the Union provided a bridge from the old to the new history. Narrative in form, based on exhaustive research in newspapers, manuscript, and archival materials, rich in original interpretations, and presented in a style always vigorous and lucid and often eloquent, The Ordeal of the Union was closer to the great narrative histories of the nineteenth century—those by Parkman, Henry Adams, and Rhodes—or to those English models Mr. Nevins so admired—those by Macaulay, Lecky, Churchill, and the two Trevelyans—than it was to the new technical history that (with his encouragement) many of his own students were already writing. Allan Nevins was in many ways a stout traditionalist, but he was also—witness his sponsorship of oral history—an innovator, and one of his last articles celebrated the new techniques which were even then transforming much of the conventional history that he had written.

Not content with this prodigious output of original work, Professor Nevins undertook editorial activities sufficient to occupy the full time of most scholars. While still editor on the World he wrote a minor classic of social history—American Social History as Recorded by British Travelers (1923). In 1927 he began to make available some of the more famous diaries of American history: that of the New York City social leader, Philip Hone, in two volumes; those of Presidents Polk and John Quincy Adams in single volumes; two volumes of the journals of Toledo’s Brand Whitlock; and, most valuable of all, the massive four-volume diary of George Templeton Strong. Alongside these stand a dozen or so other collections of letters and public papers—the previously mentioned volumes of Walter Lippmann’s editorials, the letters of Grover Cleveland and Abram Hewitt, and a selection from the public papers of John F. Kennedy. And during the whole of Nevins’s academic life he exercised close editorial supervision over several major series: the American Political Leaders series, the new Chronicles of America series, the Nations of the Modern World series, Heath’s College and University History series, and, in the last decade of his life, the fifteen-volume Civil War Centennial series.

This most industrious of scholars was also the most dedicated of teachers. For thirty years he lectured to large classes of graduate students and, in his overcrowded seminars, guided literally scores of others through dissertations and into scholarly careers-dissertations which he supervised and edited with meticulous care, careers which he encouraged with ceaseless benevolence, for his relationship with his graduate students was always in loco parentis. His teaching was not confined to Columbia University. He lectured widely, taught for one year in the universities of Australia, and twice held the Harmsworth Chair of American History at Oxford University, where he managed to penetrate the formidable barriers of traditionalism and introduce some long-needed reforms.

Professor Nevins had a third career, which might be characterized—in no pejorative sense—as entrepreneurial. Ceaselessly concerned for the reputation and well-being of Clio, he turned much of his energy to celebrating her virtues, protecting her from those he thought her enemies, and advancing her cause. There was a Napoleonic quality about Nevins’s combination of grand strategy and tactics in these undertakings. We can recall him looking out from his eyrie on the sixth floor of Fayerweather Hall—that vast book-lined and paper-strewn room where the very air vibrated with his energetic presence—looking out not merely over the campus of Columbia University but over the whole broad realm of history and planning forays and excursions to assure its prosperity and its triumph. Thus he launched a campaign to build up the history collections of the University library and brought it to a fortunate conclusion by obtaining for the University the munificent Frederic Bancroft Fund. Thus he campaigned to introduce more American history into the high schools, and he succeeded in influencing legislation everywhere in the nation. Thus he championed the potentialities and the dignity of business history; in his own voluminous writing and those of his associates and students and in the creation of business archives, he did much to give respectability to that heretofore neglected enterprise. Thus he worked long to establish a popular journal that would present American history as Harper’s, the Century, and Scribner’s of the late Victorian era had done; though he had little help here from his professional colleagues, he succeeded in founding the Society of American Historians and launching the now widely read American Heritage, whose counselor he remained to the end of his life.

Doubtless most important of all was Nevins’s role in creating—or reviving—modernizing, systematizing, and institutionalizing oral history. Oral history itself was as old as Homer and the Icelandic sagas; what Professor Nevins envisioned was a systematic and professional exploitation of personal recollections of men and women who had played public roles. What would we not give, he used to ask, for Washington’s account of his services in the Revolution, for Lincoln’s detailed observations on his presidency. It was an argument that persuaded President Truman, and scores of others, to provide thousands of pages of oral history to eager tape recorders. The Bancroft Fund enabled Mr. Nevins to inaugurate this project at Columbia University; soon he had worked out an effective technique and trained a corps of younger scholars in that technique; soon the oral history project developed into a formidable and invaluable archive. The idea spread from academy to academy, to private associations like the medical associations and the Red Cross, to government bureaus, and to corporation offices until within two decades oral history became a new dimension of historical research at home and abroad.

In 1958 Mr. Nevins retired, formally, from Columbia University and took the post of senior research associate at the Huntington Library. There he devoted his still abounding energies to building up the library and manuscript collections of that institution, helping to make it pre-eminent in many fields of history and literature, and to his own writing. He was, by long training, a bookman and a book collector; his private library, much of which he disposed of in his own lifetime, numbered well over twenty-five thousand volumes.

Allan Nevins had a distinguished public as well as scholarly and academic career. During the Great War he served as cultural attache to the United States Embassy in London, and later was a kind of cultural ambassador to Australia. He was an adviser to presidents and statesmen—General Eisenhower, Cordell Hull, Herbert Lehman, John G. Winant, Adlai Stevenson, and John F. Kennedy among them. He rescued the Civil War Centennial Commission from the hands of antiquarians and party hacks. He served, at various times, as president of the Society of American Historians, president of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, fellow of the New-York Historical Society, and historical adviser to the Sixth Fleet. Nor should we fail to recall that shortly after his retirement from Columbia University he gave that institution, out of his literary earnings, half a million dollars to endow a chair of American economic history—a chair that now bears his name.

In all this Allan Nevins sounds like an institution and, indeed, had he not been so ebullient and so dynamic, observers might have mistaken him for that. No mere formal account of his career does justice to his affluent personality—to that enthusiasm for learning so contagious that few could resist its importunities; to that single-minded practicality which had no time for academic dalliance but concentrated on getting results; to that tireless tenacity which overcame obstacles of nature and of human nature and brought his own enterprises and those of his students to fulfillment; to that generosity, moral and intellectual even more than material, which left no room for envy or malice (in almost forty years of intimacy I never heard Allan make a malicious remark about a fellow scholar); to that homespun simplicity and unpretentiousness which permitted him to take on whatever tasks came to hand that he thought worth doing, to accept old and young with equal fellowship, to extend help to amateurs as readily as to fellow scholars; to a capacity for friendship and affection which brought him the devotion of friends in almost every segment of society—academic, journalistic, political, business, military, and merely neighborly. Somehow Nevins found time, too, for an immense correspondence, not only with fellow scholars and graduate students, but with the exalted world of statesmen, with the fluctuating world of business, with editors, novelists, poets, social workers, and old friends. A collection of some fifty thousand of these letters now awaits the student of American cultural history in the archives of his beloved university.

The pattern of Allan Nevins’s private, social, professional, and public life was ever harmonious. That same harmony will be found in the historical monument he left behind him—a monument that will, for many years, cast its long shadow across the historical landscape which he surveyed, explored, cultivated, and embellished with such devotion and passion.—Henry Steele Commager, Amherst College

Bibliography

Illinois, by Allan Nevins. New York: Oxford University Press, American branch, 1917.

The Evening post; a century of journalism, by Allan Nevins. New York: Boni and Liveright, 1922.

American social history as recorded by British travellers, compiled and edited by Allan Nevins. New York: H. Holt, 1923.

The emergence, of modern America, 1865-1878, by Allan Nevins. New York: Macmillan, 1927.

Polk; the diary of a president, 1845-1849, covering the Mexican War, the acquisition of Oregon, and the conquest of California and the Southwest, edited by Allan Nevins. London, New York: Longmans, Green, 1929.

Henry White; thirty years of American diplomacy, by Allan Nevins. New York, London: Harper & Brothers, 1930.

American social history as recorded by British travellers. New York: H. Holt, 1931.

Interpretations, 1931-1932, by Walter Lippmann, selected and edited by Allan Nevins. New York: Macmillan, 1932.

Grover Cleveland; a study in courage, by Allan Nevins. New York: Dodd, Mead, 1932.

A modern reader; essays on present-day life and culture, selected and edited with the collaboration of Walter Lippmann and Allan Nevins. Boston: New York: D. C. Heath, 1936.

Hamilton Fish; the inner history of the Grant administration, by Allan Nevins, with an introduction by John Bassett Moore. New York: Dodd, Mead, 1936.

Selected writings of Abram S. Hewitt. New York: Columbia University Press, 1937.

The gateway to history, by Allan Nevins. New York, London: D. Appleton-Century, 1938.

The heritage of America; readings in American history, edited by Henry Steele Commager and Allan Nevins. Boston: Little, Brown, 1939.

Frémont, pathmarker of the West, by Allan Nevins. New York, London: D. Appleton-Century, 1939; Reprint, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1992.

The life and writings of Abraham Lincoln; edited, and with a biographical essay by Philip Van Doren Stern; with an introduction, “Lincoln in his writings,” by Allan Nevins. New York: Random House, c1940.

John D. Rockefeller: the heroic age of American enterprise, by Allan Nevins. 2 vols. New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1941, 1940; Reprinted as Study in power: John D. Rockefeller, industrialist and philanthropist, with a foreword by Robert Bezilla. Collector’s ed. Norwalk, Conn.: Easton Press, c1989.

America in world affairs, by Allan Nevins. London, New York: Oxford University Press, 1941.

America: the story of a free people, by Allan Nevins and Henry Steele Commager. 1st ed. Boston: Little, Brown, 1942.

A select bibliography of the history of the United States, compiled by Allan Nevins. London: Printed for the Historical Association by Wyman & sons, 1942.

The making of modern Britain, a short history by John Bartlet Brebner and Allan Nevins. New York: W.W. Norton., 1943.

The United States and its place in world affairs, 1918-1943, edited by Allan Nevins and Louis M. Hacker. Boston: D.C. Heath, 1943.

A century of political cartoons; caricature in the United States from 1800 to 1900, by Allan Nevins and Frank Weitenkampf. With 100 reproductions of cartoons. New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1944.

Old America in a young world, by Allan Nevins. New York: Newcomen Society of England, American Branch, 1945.

Sail on; the story of the American merchant marine, by Allan Nevins. New York: United States Lines Company, 1946.

Ordeal of the Union. 2 vols. New York, Scribner, 1947; Reprint with a new introduction by James M. McPherson. 1st Collier Books ed. New York: Collier Books, 1992.

America through British eyes. New ed., rev. and enl. New York: Oxford University Press, 1948.

The greater city: New York, 1898-1948, ed. by Allan Nevins and John A. Krout. New York: Columbia University. Press, 1948.

The heritage of America; edited by Henry Steele Commager and Allan Nevins. Rev. and enl. ed. Boston: Little, Brown, 1949.

The emergence of Lincoln. 2 vols. New York, Scribner, 1950.

The New Deal and world affairs; a chronicle of international affairs, 1933-1945. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1950.

The United States in a chaotic world; a chronicle of international affairs, 1918-1933. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1950.

Diary, 1794-1845; American diplomacy and political, social, and intellectual life from Washington to Polk. Edited by Allan Nevins. New York: Scribner, 1951.

The statesmanship of the Civil War. New York: Macmillan, 1953.

Ford. By Allan Nevins with the collaboration of Frank Ernest Hill. 3 vols. New York: Scribner, 1954-63.

Hamilton Fish; the inner history of the Grant administration. With an introd. by John Bassett Moore. Rev. ed. 2 vols. New York: F. Ungar Pub. Co., 1957

Times of trial. Edited by Allan Nevins for American Heritage. 1st ed. New York: Knopf, 1958.

Essays in American historiography; papers presented in honor of Allan Nevins, edited by Donald Sheehan & Harold C. Syrett. New York: Columbia University Press, 1960.

Lincoln: a contemporary portrait, edited by Allan Nevins and Irving Stone. 1st ed. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1962.

The State universities and democracy. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1962.

Herbert H. Lehman and his era. New York: Scribner, 1963.

Abram S. Hewitt, with some account of Peter Cooper. New York: Octagon Books, 1967, 1935.

The price of survival. 1st ed. New York: Harper & Row, 1967.

James Truslow Adams: historian of the American dream. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1968.

The diary of John Quincy Adams, 1794-1845: American diplomacy, and political, social, and intellectual life, from Washington to Polk. Edited by Allan Nevins. Memoirs of John Quincy Adams. New York, F. Ungar Pub. Co., 1969, 1951.

American press opinion; Washington to Coolidge. A documentary record of editorial leadership and criticism, 1785-1927. 2 vols. Port Washington, N.Y.: Kennikat Press, 1969.

The American States during and after the Revolution, 1775-1789. New York: A. M. Kelley, 1969.

Ponteach; or, The savages of America; a tragedy. With an introd. and a biography of the author by Allan Nevins. New York: B. Franklin, 1971.

The emergence of modern America, 1865-1878. New York, Macmillan. St. Clair Shores, Mich., Scholarly Press, 1972, 1927.

Allan Nevins on history, compiled and introduced by Ray Allen Billington. New York: Scribner, 1975.

A diary of battle: the personal journals of colonel Charles S. Wainwright, 1861 1865, edited by Allan Nevins; new foreword by Stephen W. Sears. 1st Da Capo Press ed. New York: Da Capo Press, 1998.

The life and writings of Abraham Lincoln, edited, and with a biographical essay by Philip Van Doren Stern ; with an introduction, “Lincoln and his writings,” by Allan Nevins. 1999 Modern Library ed. New York: Modern Library, 1999.

The burden and the glory: the hopes and purposes of President Kennedy’s second and third years in office as revealed in his public statements and addresses. John F. Kennedy, edited by Allan Nevins; foreword by Lyndon B. Johnson. Norwalk, Conn.: Easton Press, 1988.