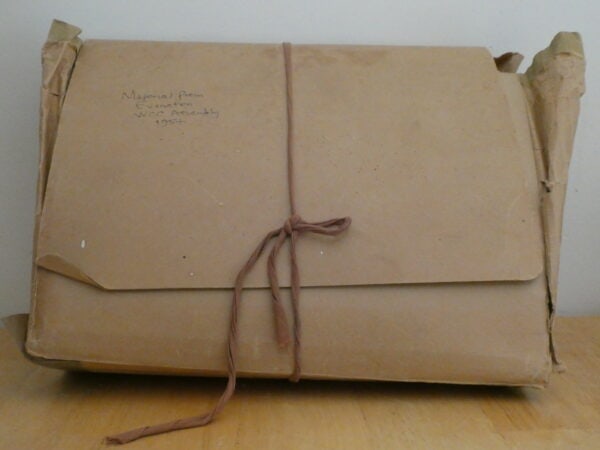

My late husband, Bill, carried around to every place he lived a battered accordion file marked “Material from Evanston WCC Assembly 1954.” He kept it in an old briefcase, separate from his working files. In it are 11 folders of meticulously organized documents from the international meeting of the World Council of Churches (WCC), an organization exploring Christian unity. The documents included his notes, which ranged from brief annotations on preprinted speeches to extensive comments on lectures, liturgies, and sermons. Also in the briefcase was a box of photographic slides from the assembly—some of them officially issued by the WCC, others his own eager snapshots of famous international figures, crowds, and scenes—and a list detailing which were which. What the collection tells us about Bill’s responses is limited. But he recorded and remembered; he was not a passive spectator.

Patricia Appelbaum

The 1954 assembly of the WCC in Evanston, Illinois, was only its second gathering, a big hopeful event in postwar internationalism. The mainline or liberal Protestantism of the mid-20th century is commonly described as “ecumenical,” focused on cross-denominational unity and cooperation. Among its institutional expressions were councils of churches, of which the World Council was the global version.

Bill was a young pastor then, serving a pair of small rural congregations, and he was intensely excited about this event. He went to great lengths to be there, traveling from California and sleeping on a friend’s sofa. Bill participated in a two-week study institute featuring some assembly luminaries that was attended by a hundred clergy and laypeople, about one-third of them from distant states and countries.

The assembly drew enormous public attention. Newspapers and magazines across the country followed it. One hundred thousand spectators attended its opening ceremony. President Dwight Eisenhower was a guest speaker, and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the Art Institute of Chicago, and several seminaries hosted complementary programs.

Along with press coverage, the assembly itself had a substantial print output. Mimeographed drafts of all the speeches were issued in advance, in several languages. There were working-group reports, public statements, publicity brochures, and take-home items. Afterward, participants received a book of photos and the set of official slides.

Bill saved most of this material in his accordion file. His annotations indicate that he anticipated applying it in his local work. “Use,” he reminded himself, on a mimeographed talk about eschatology. “Use this in PF,” he wrote, on a history of the ecumenical movement, thinking of Pilgrim Fellowship, a youth program. He wasn’t alone in his intentions: The WCC clearly meant its findings to be disseminated to local churches and communities. It provided study guides and booklets, and a press office prepared news releases for “your hometown paper[s].” A new hymn, the winner of a competition with five hundred entries, was issued in ready-to-use offprints.

This is how movement work gets done on the ground. Many forces made the ecumenical movement, but one of them—as in any social movement—was this band of irregulars. Someone caught a glimpse of the great Toyohiko Kagawa or Martin Niemöller and displayed the snapshots in a community slideshow. Someone took time from a busy career to absorb an intensive lecture series. Someone brought home those statements and study guides to share with small churches in Indiana and Arkansas and California. People sang a new song together.

Bill didn’t last much longer as a pastor. The following year, he entered a doctoral program that led to a teaching career in the United States and overseas. One of the things he brought with him—embodied in his accordion file—was this direct encounter with an international, theologically diverse, and emergent postcolonial Christianity. It wasn’t his last, or anyone else’s.

Patricia Appelbaum is a historian of American liberal religion.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.