Before the crack of dawn, the floodlights were turned on and the candles lit. Plumes of fragrant smoke drifted through the hot lights as men dressed in white hastily arranged plastic chairs covered in white cotton protectors. The scent of samprani (Indian frankincense) mixed with coconut coir clung to the first drops of dew falling from the pipal, papaya, and pine trees that surrounded the little lawn. Thus began the 152nd Easter Service in 2023 at All Saints’ Church, Bangalore, celebrated, as it has been for decades, in the spacious lawns adjoining the Indo-Saracenic sanctum.

David Martin

Each element of this service betokens a different part of the cosmopolitan past of the Church of South India. The candles come from the Anglican High Church, while the cloth-covered chairs are a colonial remnant, a marker of distinction for the rich and powerful (and white) who attended these churches. Samprani has biblical, kingly connotations, while coconut coir is a home remedy for the mosquito menace. Each tree marks a different aspect of the church’s religious and cultural preoccupations. The pipal, or Ficus religiosa, has a long connection to India’s religions: The Buddha and Mahavira attained enlightenment under them, and Lord Krishna was born under its shade. The papaya grows next to the church’s senior residences, and most exotic of all, the pine was planted for European members who wished to experience a more “traditional” Christmas in Bangalore’s tropical clime.

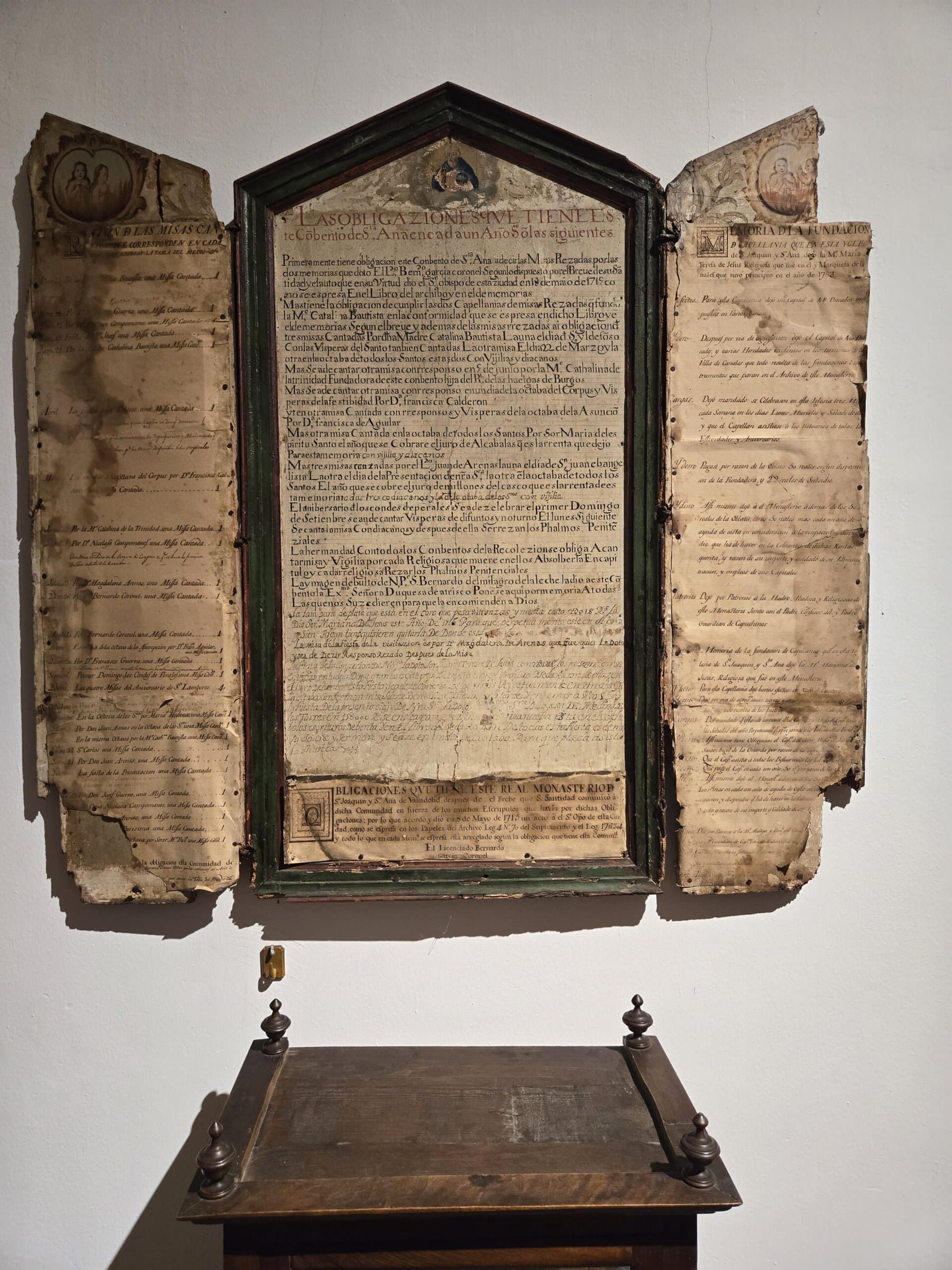

All Saints’ Church was built in 1870 by the Reverend Samuel Pettigrew, a Cambridge-educated missionary. Pettigrew had already founded two of India’s most celebrated schools five years earlier—the twin Bishop Cottons of the South, one for girls and one for boys. He went on to work around South India and traveled as far as Rangoon (in modern-day Myanmar). But the good reverend was no prelate of a golden colonial establishment; in fact, he rarely had many funds and instead relied on the goodwill of local and colonial officials to get his projects off the ground. His original plan was to build the schools and the church simultaneously, but lack of funds delayed the latter. Eventually, the celebrated architect Robert Chisholm (creator of the so-called Indo-Saracenic style of architecture) worked on the church, though with no record of payment, it seems it may have been a charitable endeavor.

The church and its sister institutions were not built on egalitarian values. They served the large cadre of retired European soldiers who could no longer fit into the grander confines of St. Mark’s Cathedral (which was designed to be a miniature version of London’s St. Paul’s). However, the church registers show another side to the story—many of these soldiers had Indian wives, and it was not long before a steady trickle of Indian converts started filing in, remarkably, without much fuss. Perhaps out of sheer necessity, the church, which had always had prestige and penury in equal measure, was forced to crack open their doors to Indians, both Christian and non-Christian. These were the people who looked after the church grounds, and it was thanks in no small part to them that this now centuries-old establishment survived the uproar of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

As “payment” for its “tolerance,” the people of Bangalore bequeathed to the church a unique history inscribed on every tree in the garden and every shingle on the roof. It is not the story of a heartwarming egalitarian foundation, or of a glorious revolution to create an inclusive and equal future. Rather, it is a curious, almost quaint tale of a series of socioeconomic accidents that coalesced into a church.

David Martin is a PhD researcher at the University of Cambridge.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.