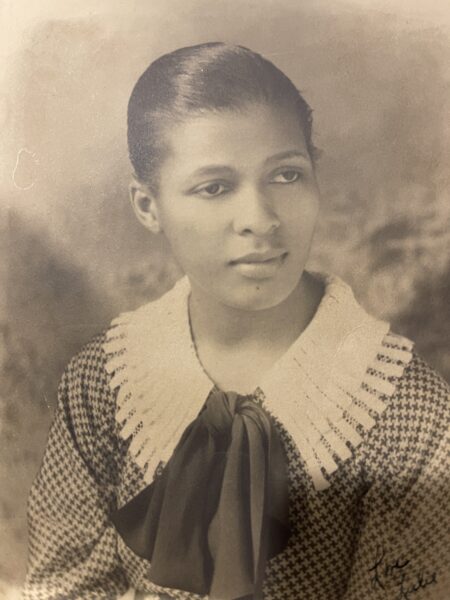

John I. Jackson Family Collection, used with permission

When Lulu Merle Johnson received her history PhD from the University of Iowa in 1941, she made newspaper headlines as the first African American woman to earn a doctorate in Iowa and from the University of Iowa. She had already launched her professional career as a professor, but the occasion nonetheless marked a turning point in her intellectual journey.

Born in 1907, she was the fifth of six children born to Richard and Jeannette Johnson, who were but one generation removed from slavery. She grew up in Gravity, a small town in rural southwest Iowa, surrounded by a large extended family. After the Civil War, her grandparents had migrated from Tennessee to Kentucky to Illinois and then to Taylor County, Iowa, where they purchased farmland and put down roots in the early 1880s.

Johnson followed a first cousin and a brother to the University of Iowa, earning her BA and MA in 1930. She then left Iowa for the Deep South, where historically Black colleges and universities would hire Black faculty. After a one-year appointment at Talladega College, she moved to Tougaloo College. While teaching there, she began work on her doctorate, spending 1934–35 in residence at Iowa, and, with the aid of a General Education Board fellowship from the Rockefeller Foundation, spent a second year in residence to complete her studies and receive her PhD in August 1941.

During her decade at Tougaloo, and while working on her doctorate, Johnson developed what became her signature course, The Negro in American Life. It represented a remarkable, dramatic departure from the traditional training she received at Iowa. Her dissertation, “The Problem of Slavery in the Old Northwest, 1787–1858,” examined the contest between proslavery and antislavery forces in antebellum Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois through a Turnerian lens to argue that the “economics of slavery failed to establish a permanent tie between the Upper South and the frontier democracy of the Old Northwest.” Conversely, the detailed course notebook she used for teaching The Negro in American Life reveals a diverging path of intellectual inquiry into what Caroline F. Ware called “the cultural approach to history.” The course readings included cultural anthropology, sociology, and political economy, and at least half the authors were African American. Her lecture topics began by examining race and culture concepts and then traced the Black experience in American history from the African slave trade to the mid-20th century. After World War II, she began to examine the postwar Black experience in light of Franklin Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms, and she asked students to envision a “democratic profile for the future” that fully included African Americans.

In a general sense, development of this course aligned with the flowering of the New Negro movement, but two specific forces seem to have influenced its particular content. One was sociologist Edward Reuter, whose specialty was race relations. Johnson took three of his courses as a graduate student, and his works appear in her course reading lists. The second was moving to the Deep South. While she was adept at managing Iowa’s subtle patterns of racial discrimination, she was shocked by the virulent racism of the South, particularly how it strangled the education of African American youth. The latter provoked a streak of anger, and The Negro in American Life seems to have been her counteroffensive: centering the Black experience in American history as a means of instilling race consciousness among her students.

Johnson taught this course throughout her career, thus putting her in the forefront of creating the academic field of Black history/studies. She launched it at Tougaloo in 1941 before moving to West Virginia State College (now West Virginia State University) as an associate professor in 1942. In 1946, she became dean of women at Cheyney State Teachers College (now Cheyney University). Except for a short stint as chair of the history department at Florida A&M University in the late 1940s, she remained at Cheyney until her retirement in 1971. For most of those years, she held a dual post as professor of history and dean of women. In retirement, Johnson traveled extensively and frequently hosted family and friends at her home in Millsboro, Delaware. She died in 1995 at age 88.

In 2021, Johnson County, Iowa, adopted Lulu Merle Johnson as its eponym; she replaced Richard Mentor Johnson, vice president under Martin Van Buren. A statue and permanent interpretive exhibit on Johnson’s life is in development in Iowa City.

Rebecca Conard

Middle Tennessee State University (emerita)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.