The modern battery was invented at the turn of the 19th century and quickly became the power source behind new communications, industrial, and scientific technologies. But the global history of the battery is also a story of how batteries were adapted around the world, how they became part of divergent cultural vocabularies, and how people used knowledge about batteries to demonstrate their command over modern technology.

Courtesy Rekhta Ebooks

In late 19th-century British colonial India, batteries became the subject of poetry. Verses about how to make and use a battery were featured in an 1880 Urdu-language manual on electroplating, the practice of coating an object in a layer of metal through an electrical current. Producers of everyday objects like kitchenware, surgical tools, and jewelry used electroplating to coat a base metal with a more precious, attractive, or less corrodible finish. Between the 1870s and 1910s, electroplating became a popular topic in Urdu-language technical writing.

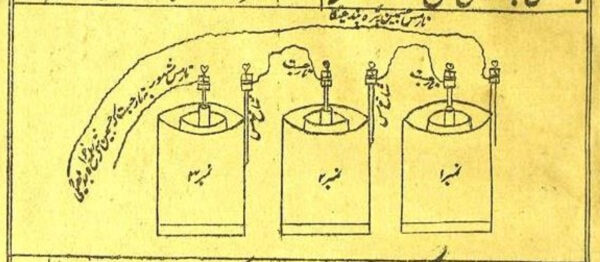

The 1880 manual Jāmaʿ-yi tarākīb-i talmīʿ (Collection of techniques of plating) was published in the northern city of Lucknow in 1880. Across 64 pages—written entirely in verse—it described how to create multiple styles of battery and use their electric charge to electroplate. Its rich illustrations explained how to wire together multiple batteries to increase the longevity of their charge. Verses accompanying this image explained: “Connect the zinc wire of the first battery / With the copper node of the second / Oh friend! If it is fastened, then both batteries / Undoubtedly will become joined together.” The poem goes on to describe connecting “as many batteries as you wish” and then how to connect the final battery to the object to be plated. The illustration reinforced these steps, depicting three numbered batteries connected by zinc wires attached to copper nodes.

Versified manuals served multiple purposes. Such verse established the author’s literary and industrial prowess. The Jāmaʿ-yi tarākīb-i talmīʿ was attributed to Jawaharlal, an author who used the pen name Shaida (“lover”) for his poetry. Shaida worked for the engineering department of Udaipur state. In the introduction, he portrayed himself as promoting the technical capacities of the state—and of India more widely—while also participating in regional courtly culture by demonstrating his talent for poetic composition using new topics and terms.

Such poetry also promised readers a role in the rapidly shifting systems of authority in colonial India. Urdu electroplating manuals first circulated among middle-class hobbyists and aspiring industrialists, who often came from privileged families. In the 19th century, some caste-dominant communities retrenched their own social positions by demonstrating mastery and authority over technologies associated with the colonial state. But the manuals also became popular among artisan metalsmiths, many from marginalized caste backgrounds and laboring communities. Poems about making and using batteries likely also circulated within artisan communities with varying literacy levels. By reciting and sharing these practical, educational verses, Urdu speakers came to understand a new technology. Some metalsmiths even wrote their own manuals. These positioned electroplating within longer genealogies of regional metal plating techniques, arguing that laborers’ forms of material and technical knowledge remained relevant in the colonial economy.

The Jāmaʿ-yi tarākīb-i talmīʿ addressed both potential audiences. It celebrated the tacit skills of artisans and their ability to master new techniques with their knowledgeable hands, but it suggested that such skills would be of interest for hobbyists too. Shaida skirted questions of class- and caste-based authority over technology. Instead, he maintained that this knowledge was important for all Indians, in that it could help them challenge the economic and industrial dominance of British colonialism. By adapting knowledge about how to make and use batteries into vernacular poetic traditions, Indian Urdu poets gave the battery new and localized social and political relevance.

Amanda Lanzillo is assistant professor in the Department of South Asian Languages and Civilizations at the University of Chicago and an ACLS Fellow in 2024–25.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.