When economist Paul Krugman was asked about Trump’s drastic change in the tariff on April 5, he said it was “like nothing we’ve ever seen before.” Certainly a president changing worldwide tariffs using AI is unprecedented, but in other ways this is nothing new. Since the 19th century, US government actions have led to drastic changes in international trade and finance, and the results have led to depressions more than once.

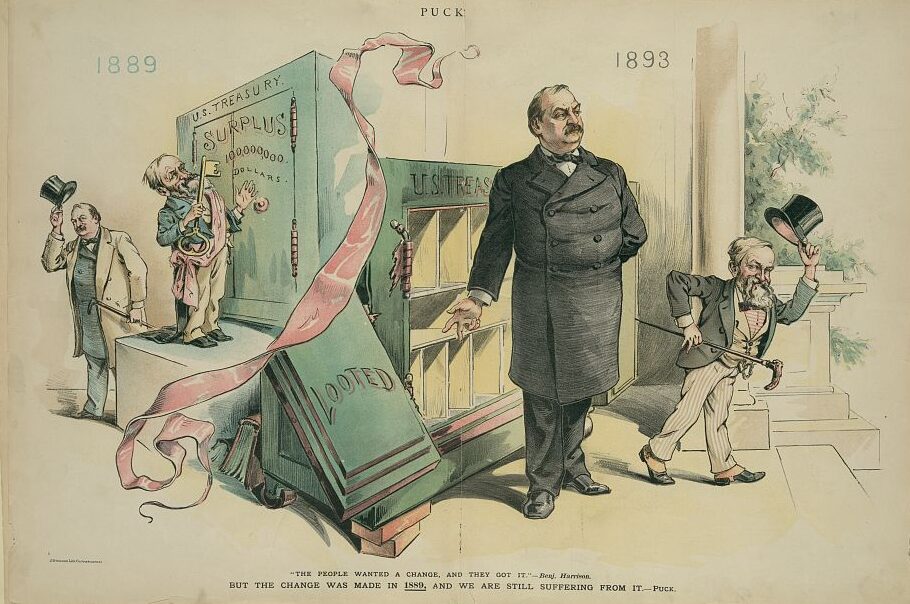

Benjamin Harrison (left) presided over tariff alterations that drew nearly all of the 100 million dollars in gold that the US Treasury possessed in 1889. Four years later, Grover Cleveland (right) began his second nonconsecutive term, by which time the treasury was empty, threatening the US dollar on international markets. Puck (1893) / Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

One time, this change came almost entirely from the executive, in 1837. But it also arrived from radical changes brought by Congress and approved by presidents in 1816, 1890, and 1930. And in all four cases, the result was not recessions but depressions. These came in 1816–20, 1837–43, 1893–95, and 1930–33. All four depressions—which I define as two or more years of declining GDP—have started this way. But they are unfamiliar to most Americans, economists included. Almost no one alive has lived through them, because the last one ended in 1933. But these events can help us understand how to moderate them or at least learn to cope.

In 1816, at the end of the Napoleonic Wars, British traders dumped hundreds of tons of half-finished woolen goods at “prices, monstrous cheap” in New York, Baltimore, and Philadelphia. Merchants and woolen manufacturers cried foul, and Congress responded with the American Navigation Acts in 1816, sharply limiting trade from British ships. Britain retaliated with Orders-in-Council that prevented US ships from trading in the British Caribbean. The loss of the Caribbean trade led wheat prices to drop by 50 percent in 1818, turning a postwar recession into a national depression. The long-term effect of the US–British trade war was to dampen US grain exports and buoy up US cotton exports. No single act of Congress contributed more to American capitalists shifting their investments to slavery and cotton plantations.

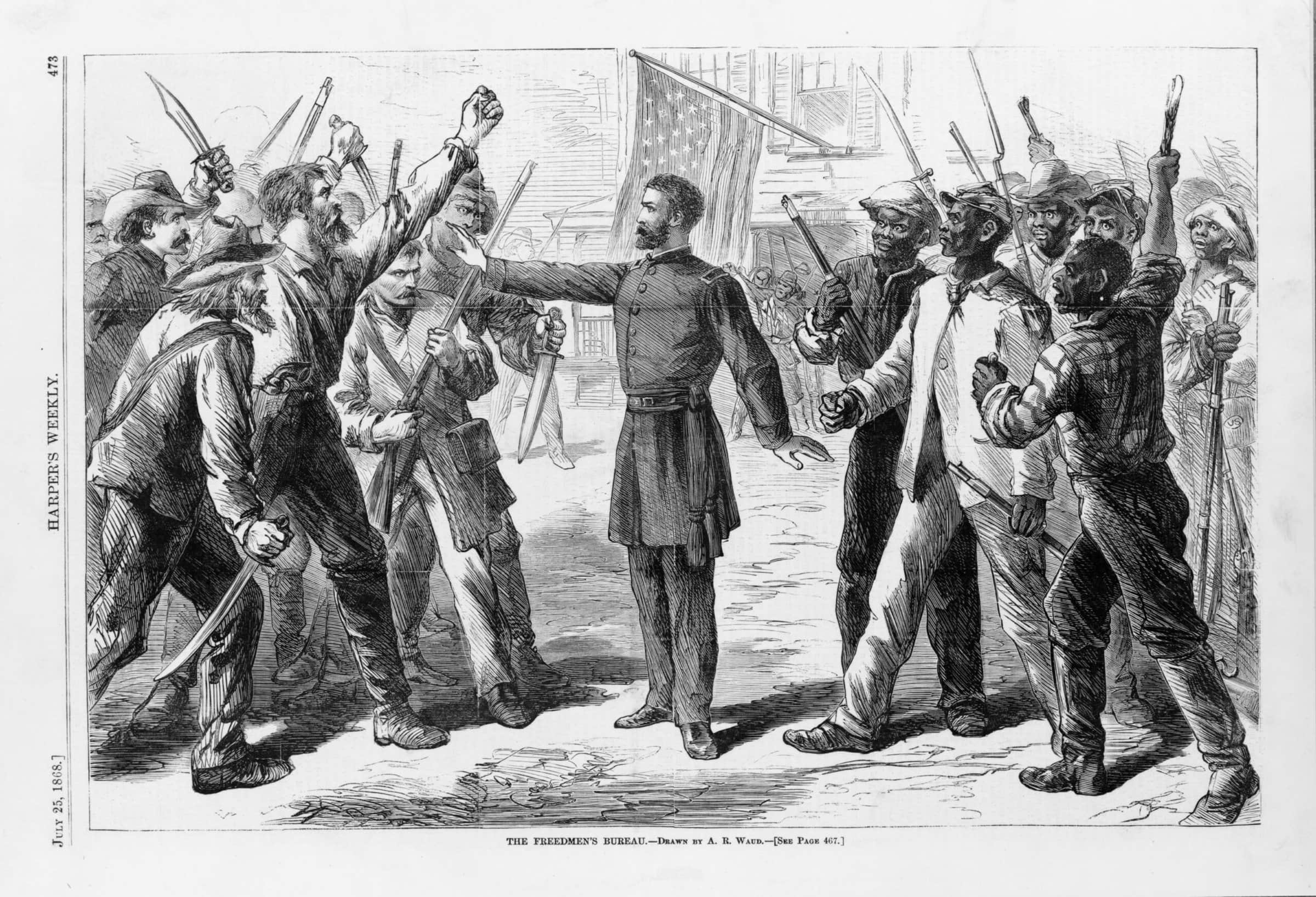

British banks, resenting the imperious Americans but seeing the opportunities offered by slavery in the richly productive Lower South, then built up a complex cotton-for-credit exchange across the Atlantic. Most English banks did not invest their customers’ deposits in government bonds (the standard for the time) but rather held long-term bills of exchange to be paid for with American cotton. Those bills of exchange were the credit that English banks then used to prop up regional banks in the US South. The credit funded the transportation of enslaved people in the Upper South to slave markets in New Orleans, Savannah, and Mobile. The credit finally returned after the harvest with the transit of picked cotton back to Britain.

The Bank of England cut off the British banks, raised the bank rate, and plunged the US into a depression that lasted six long years.

The president whose actions most resemble Trump’s is Andrew Jackson, who thought he could somehow renegotiate this trade in 1837, and so inaugurated a new depression that flowered after he left office. He tried to defund Britain’s role in this credit chain by removing deposits from the Second Bank of the United States (which facilitated this Atlantic cotton trade) and demanding gold for US land sales. This was, in the words of Trump, “a deal like no other,” mostly to support Jackson’s slaveholding friends who had discovered gold in North Georgia and western North Carolina. But that gold was not nearly enough to cover these complex transactions. The Bank of England, sensing that too much gold was being exported to the US to cover these transactions, cut off the British banks, raised the bank rate, and plunged the US into a depression that lasted six long years.

After the Civil War and the end of slavery, the so-called Reed Rules instituted in 1890 gave House Republicans tremendous authority and strongly limited the power of the dissenting Democrats. Republicans took advantage by radically altering tariffs, nearly doubling them on imports while drastically lowering them for sugar. Import tariffs brought in less and less money, while the lowered sugar tariffs worsened the situation. The loss of revenue brought the US Treasury to the brink of bankruptcy, leading European investors to divest from US government and railroad debt because they worried that both debts would be paid off in depreciated dollars. That depression lasted from 1893 to 1895.

The loss of revenue brought the US Treasury to the brink of bankruptcy.

Finally in 1930, Republican congressmen Reed Smoot and Willis Hawley raised tariffs on agricultural imports (to please farmers) and industrial imports (to please manufacturers). They believed somehow that American exports would not be affected. While there were plenty of international causes for the Great Depression that followed—including German World War I war debts and a lending spree to German cities that to this day have never been repaid—Smoot and Hawley could be seen as the prime movers in bringing a sharp depression to the United States.

So while US tariffs leading to global market turmoil is not new, what is unprecedented now is the quiescence of Congress. After all, revenue tariffs are supposed to start in the House of Representatives, according to the Constitution. President Trump claims that a “war” on fentanyl justifies his use of the war powers in the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977, a shocking overreach. We are watching unprecedented actions by the president to be sure, but the result of radical changes in tariffs and international trade generally should be familiar to anyone who knows American financial history. Unfortunately, Congress appears to have slept through those lessons.

Scott Reynolds Nelson is the Georgia Athletics Association Professor of History at the University of Georgia. He is the author of A Nation of Deadbeats: An Uncommon History of America’s Financial Disasters (2012) and Oceans of Grain: How American Wheat Remade the World (2022).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.