This handout was created for the AHA’s March 13, 2025, Congressional Briefing on the history of deportation. Panelists Hidetaka Hirota (Univ. of California, Berkeley), Ana Raquel Minian Andjel (Stanford Univ.), and Yael Schacher (Refugees International) discussed policies concerning immigration and deportation throughout US history, including the origins of deportation policies, the role of race and political ideology in deportations, and evolving American asylum policies.

The recording of the briefing will air on C-SPAN on April 19 at 3:30 p.m. EST.

Chronology

1639 – Colonial Massachusetts law authorized towns to remove poor people who had no legal settlement in the town.

1683 – Colonial New York law authorized local officials to send transient beggars to “the country from whence they came.”

1794 – Massachusetts state law allowed for the expulsion of any pauper without legal settlement in the state to “any other State, or to any place beyond [the] sea where he belongs.”

1798 – The Alien Act authorized the president to arrest and deport foreign nationals whom he deemed dangerous to the peace and security of the United States.

1850 – Massachusetts immigration officials were authorized to deport foreign paupers from the United States.

1875 – The US Supreme Court declared state passenger laws in New York, Louisiana, and California unconstitutional.

1882 – The Chinese Restriction Act excluded Chinese laborers, with a provision for the deportation of Chinese who unlawfully entered the United States.

1882 – The Immigration Act excluded the poor, people with mental illness, and criminals.

1891 – The Immigration Act added people likely to become public charges, people with contagious diseases, polygamists, contract workers, and assisted immigrants to the excludable class. The act also provided for the deportation of foreign nationals found to have entered the United States unlawfully within a year after arrival.

1892 – The Geary Act required Chinese in the US to obtain a Certificate of Residence. Those who failed to do so would become deportable.

1924 – The Immigration Act introduced the national origins quota system, starting quantitative immigration restriction. It also introduced a consular control system and suspended virtually all Asian immigration.

1930s (Great Depression) – One of the most extensive mass expulsion campaigns in US history, on the premise that Mexican migrants and US-born Mexican Americans were responsible for significant aspects of the nation’s economic miseries. By the late 1930s, 2 million people had been expelled to Mexico; 60% are estimated to have been US citizens.

1942–64 – The Bracero Program, a guest worker program allowing temporary labor from Mexico, issued over 4.5 million contracts in 22 years. The program led to increased unsanctioned border crossings. More people wanted to join than there were available slots, leading to undocumented migration. Returning Braceros encouraged others to migrate.

1954 – The Immigration and Naturalization Service launched Operation Wetback, a paramilitary campaign to expel Mexican migrants. Over 1 million people were apprehended; many families were separated by deportation. Operation Wetback reduced unauthorized crossings; the government replaced those workers—because of employer demands—with legal guest workers through the Bracero Program.

1964 – Congress ended the Bracero Program. Mexican workers accustomed to US employment continued migrating—now without authorization.

1965 – The Immigration and Nationality Act (also known as the Hart-Celler Act)

- Replaced the race- and nationality-based quota system that had been in place since 1924 with numerical quotas on migration from all countries, including on independent countries in the Americas for the first time.

- Created a preference system that focused on immigrants’ skills and family relations with citizens or US residents and exempted immediate relatives of US citizens from the quota.

1980 – The Refugee Act

- Provided a permanent and systematic procedure for the admission of refugees of special humanitarian concern to the US.

- Incorporated the UN Refugee Convention definition of a refugee into US law.

- Mandated the establishment of procedures whereby a person at the border or in the US, regardless of status, could seek asylum.

- Prohibited return of any asylum seeker to a country where their life or liberty would be threatened.

1980s – Thousands of Central Americans fled to the US due to violence and poverty. US immigration officials refused to hear or summarily denied asylum claims from Salvadorans and Guatemalans, prompting the growth of the Sanctuary Movement and leading to a federal court settlement requiring new hearings for hundreds of thousands of asylum seekers. The US also pressured Mexico to block migrants before they reached the US border. As a result, Mexico deported more Central Americans than the US.

1986 – The Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA)

- Introduced border fortification and increased border enforcement to deter unauthorized migration. Instead of inhibiting migration, the policy changed behavior, as migrants, fearing the risks of crossing multiple times, brought their families and settled permanently. The overall unauthorized migrant population living in the United States increased.

- Granted a pathway to permanent residency to unauthorized immigrants who had lived in the US since 1982 or worked in certain agricultural jobs.

- Imposed sanctions on employers who knowingly hire unauthorized workers.

1990 – The Immigration Act

- Revised the preference categories for immigration visas (including limiting visas for low-skilled workers) and created new diversity and specialty immigrant visas and temporary visas.

- Authorized the attorney general to grant “temporary protected status” to nationals of countries suffering from armed conflicts, natural disasters, or “other extraordinary and temporary conditions.”

1996 – The Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 (IIRAIRA)

- Added penalties for immigrants who commit crimes in the United States or undocumented immigrants who stay in the US for statutorily defined periods of time.

- Created an expedited removal process, mandating detention and fast-track removal without immigration court proceedings.

2004–18 – Mexico deported 1.7 million Central Americans; the US deported 1.1 million Central Americans.

2006 – The Secure Fences Act mandated that the Secretary of Homeland Security act quickly to achieve operational control over US international land and maritime borders, including an expansion of existing walls, fences, and surveillance.

2008 – The Trafficking Victims Protection Act created visas for victims of trafficking and special screenings for unaccompanied children. Unaccompanied children from noncontiguous territories are referred to the Office of Refugee Resettlement.

2010 – Los Zetas cartel massacred 72 Central American migrants who were unable to pay the cartel. Cartel violence against Central American migrants has since escalated.

2012 – The Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) executive action enabled young adults (ages 15 to 30) brought to the US illegally as children to apply for temporary deportation relief and a two-year work permit.

2015 – Decision in Flores v. Johnson set detention conditions for families and limited it to 20 days.

2020 – Section 265 of US Code Title 42 was invoked to prohibit entry and authorize expulsion of border crossers in the name of preventing the spread of COVID-19.

The Foundations of US Deportation Policy

- Until the 1870s, immigration to the United States was administered largely by state governments. The federal government began regulating immigration during the 1870s and 1880s.

- Policies for removing migrants developed in tandem with policies for restricting migrants’ admission. Policies of deportation and border control were intertwined.

- The purposes and targets of deportation changed over time. Some of the earliest deportation laws focused on poor people. But by the early 20th century, the category of deportable people was expanded. Diverse groups of migrants could be expelled not only on economic grounds but also on medical, political, and moral grounds.

- The scope and impact of early deportation policy were limited. Before 1924, there were time limits on the applicability of deportation. The overwhelming majority of European immigrants were admitted and relatively few were deported.

- Racism was and remained a major driving force in the development of federal deportation policy.

Deportation in the 1930s–80s

- Deportations during this period affected both migrants and American citizens, often violating the rights of legal residents and citizens. They tore families apart, separating citizen children from their parents.

- Presented as measures to protect jobs and public safety, deportations generally failed to improve economic stability or public safety. They sometimes worsened security concerns by strengthening criminal organizations.

- US immigration laws and policies shaped unauthorized migration. Enforcement efforts often had unintended consequences. Policies—including deportation policies—fueled the very migration patterns they aimed to curb.

Deportation since 1980

Overall trends:

- Increased use of formal deportation proceedings, with bars on re-entry.

- Expanded reasons for deportation of noncitizens.

- More limited avenues for unauthorized immigrants to regularize their status.

- Legal limits on deportation (i.e., Temporary Protected Status, Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act), and the tension between targeting recent unauthorized border crossers for deportation even as increasing numbers of them crossed the border to legally seek asylum.

Other limits placed on implementing deportations, including:

- Resources (for adjudication, detention).

- Finding and arresting immigrants.

- Foreign relations (limiting removals).

Policy workarounds to address these limits, including:

- Expanded use of expedited removal.

- Collaboration with local law enforcement.

- Targeting particular groups and creating a hostile environment/fear.

- Pressuring other countries into accepting deportations.

Participant Biographies

Hidetaka Hirota is an associate professor of history at the University of California, Berkeley, where he teaches US immigration history and co-directs the Canadian Studies Program. He is the author of Expelling the Poor: Atlantic Seaboard States and the 19th-Century Origins of American Immigration Policy. He has published widely on the origins and early developments of US immigration policy.

Ana Raquel Minian is an associate professor of history at Stanford University. She is the author of Undocumented Lives: The Untold History of Mexican Migration (2018) and In the Shadow of Liberty: The Invisible History of Immigrant Detention in the United States (2024), as well as articles in the Journal of American History, American Quarterly, and the American Historical Review. Minian is the founder and co-director of Stanford’s Migration and Asylum Lab.

Yael Schacher is Director for the Americas and Europe at Refugees International, an independent organization in Washington, DC. Schacher has published numerous academic articles on the history of immigration law and policy and is completing a book, Exceptions to Exclusion, on the history of asylum in the United States since the late 19th century. Before joining Refugees International, Yael taught immigration history and literature at the University of Connecticut and was a postdoctoral fellow at the Institute for Historical Studies at the University of Texas at Austin.

Related Resources

September 7, 2024

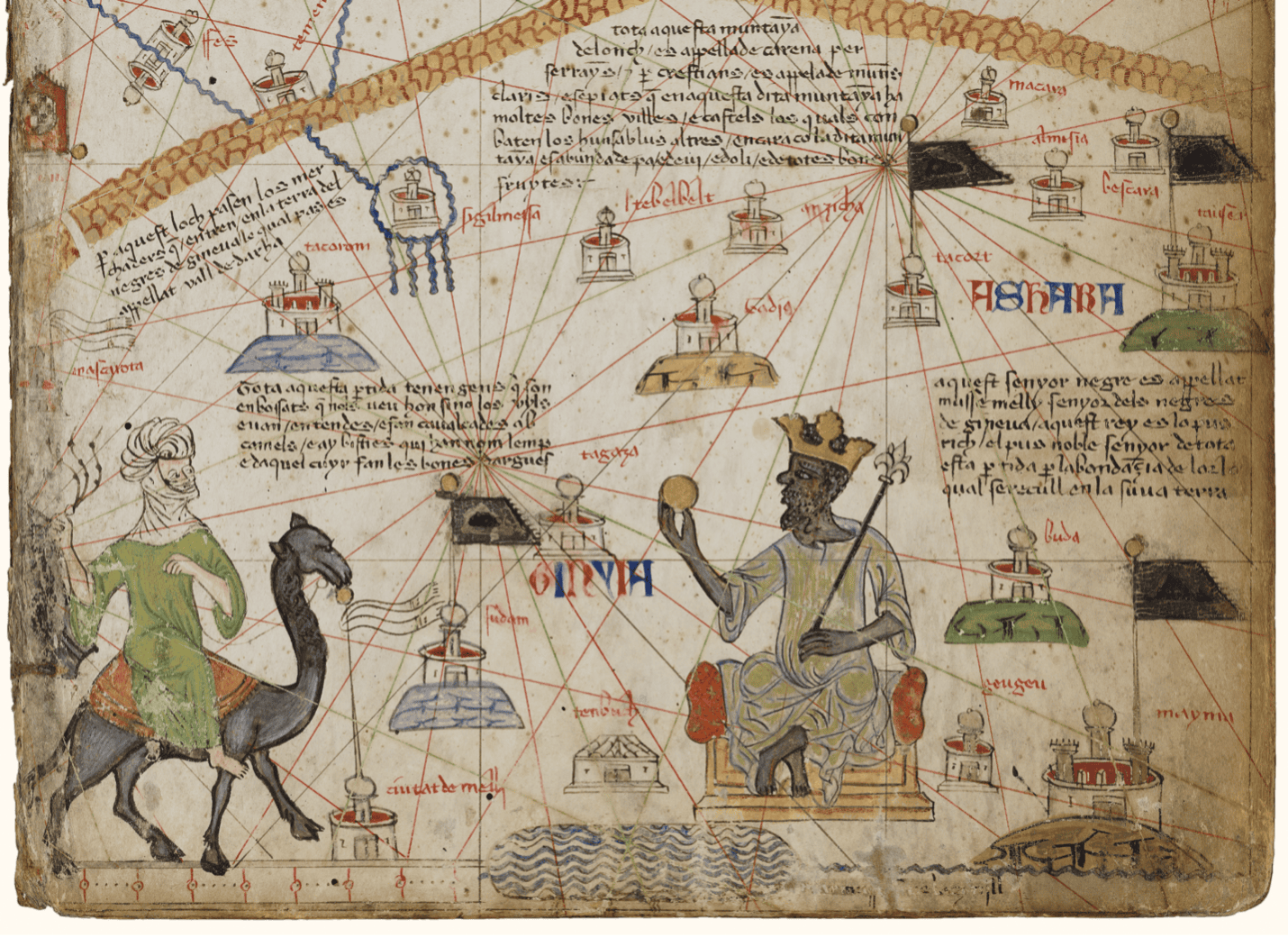

Travel and Trade in Later Medieval Africa

September 6, 2024